“Water is in constant flux, moving through the air and between forms, shape-shifting from gas to liquid to solid and back again.” – Judith D. Schwartz, “Water is a Verb,” from All We Can Save

Our problem has always come when we have tried to contain what is wild.

But, the water continues to overflow its banks because that is what water does; and, it is what we cause to happen more and more. We cause this with continued abuse of the environment. When one paves all the way up to a building, the building’s owner should stop being alarmed that the water has decided to come indoors. It was given a path to follow when what was needed was depaving and planting of vegetation, or at least installing permeable pavement.

In the 20 December 1911 edition of the Hartford Courant there was a long overview of a report made by the City Engineer, Superintendent of Streets, and Superintendent of Parks. This was regarding the question of what to do with the Park River from its mouth to Hamilton Street. In it is why Hartford had pursued mangling the river:

“Several solutions suggested, the committee reports, were rejected because they presented evident obstacles, but four different plans were considered, the first and most definite being the covering of the stream for the entire length considered, that is, from the Connecticut River to Hamilton Street. The advantage of this, aside from that of hiding the river from view, would be the gain in territory for building and highway purposes, but the plan is rejected because of the cost involved, which the committee finds would be great. The construction of a closed conduit would also give rise to unhealthful conditions from gases which would be generated, while two other objections are possible damage from excessive floods and that, if the stream were covered in, it would define its location and treatment for all time unless the entire first cost of the work was thrown away.”

Here, they understood that this level of change would be exceptionally difficult to reverse, and that it raised concerns about health. At the same time, they expected that it would either contribute to floods or be damaged by them. Nothing in this possible solution suggested it as a way to prevent floods. It’s all spelled out right there: they considered enclosing the Park River for the purpose of highways and real estate.

“The second general method of treatment was one which contemplated many re-locations of the present bed of the river to gain additional width of streets and shorter courses for the river, together with a possible quickening of the current and a gain in the fall, which would cause the water to run off more quickly, this increasing its cleaning power. This plan, too, was rejected because of the expensive, as the cost of excavation would be large and the necessary structures which would be required would be many and expensive. The plan was also open to the objections urged against the previous plan, that existing structures such as the bridge near Union Station, the Ford street bridge and the Hoadley Memorial bridge, rendered a relocation impracticable.”

In case you missed it the first time, the motivation for messing with nature was to expand streets. They recognized that large scale changes would be expensive and challenging because of the modifications they had already made to the environment.

“The third general plan, which was the most difficult to reject, was the treatment of the river for its entire length by retaining walls built on conventional lines and the paving of the riverbed itself; in other words, the reduction of the river to a canal or aqueduct, with the bed at all times accessible for cleaning. This plan, too, was rejected, first on account of the cost, as the foundation of the retaining walls would be very expensive. A second reason lies in the scenic effects; straight retaining walls on conventional lines would give an effect at once severe and unattractive, while a third reason would be the impracticability of making the walls consistent with existing structures.”

They knew that this treatment would be ugly, yet that is what you can find today on the section from just north of Hamilton Street to the area of where Pulaski Drive intersects with Brookfield Street. How accessible the bed is for cleaning remains up for debate. Much of the river is fenced. There are steep inclines. I have seen little evidence that any cleaning happens. Go stand on the sidewalk of the Hamilton Street bridge and tell me what you observe over the course of a year. What that cleaning would involve was unclear, though it sounded like occasional dredging rather than steady maintenance.

“The final method of treatment, which is the one recommended, is, the committee says, a combination of all the previous ones and is outlined as follows: From the Connecticut River to Front Street the river is considered a navigable stream with an idea to its future development for docks and shipping. There are two drawbridges across the river in this section but no great change in these will be necessary and the development of the river banks can be left to such time as the necessity for such treatment arises.”

“From the west side of Front Street to the east side of Main Street it is proposed to cover the river with a permanent structure leaving a waterway so large that no flood can surcharge it. This treatment does away with the possibility of any parking on the south side of Arch Street opposite the proposed municipal building but the establishment of any such parkway would only transfer the unsightly condition from the south side of Arch Street to the south side of the river and it is visionary, so the report says, to think of the buildings on the north side of Shelton Street as removed for park purposes.”

What is often overlooked in conversation about the Park River’s mutilation is that it’s not merely that they destroyed a river. They also used it as an opportunity to do a little of what was called “slum clearance.” The housing on the north side of Shelton Street had been tenements. If you didn’t catch what was written above, it’s that by removing one thing they considered an eyesore (Park River) people would then more easily notice another so-called eyesore (tenement housing).

Should housing ever have been built right up against the river? No.

Could healthier housing have benefited those occupying it, many of whom were new immigrants? Yes.

Were either of those questions part of the conversation? Of course not.

During this era, Hartford’s population was growing. In 1900-1910, Hartford had almost a 24% increase in its population. The busiest year for immigrants entering via Ellis Island, 1907, had been recent to the Park River burial and tenement removal discussion.

You have to wonder.

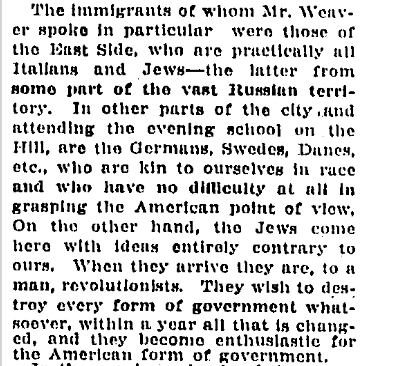

Or, you have to just read other accounts of how immigrants were considered in this era. In 1908, the Hartford Courant covered a talk given by Superintendent Thomas S. Weaver. The very same one that Weaver High is named after. This article begins in a way one thinks might be progressive. They even bragged how Weaver’s perspective on immigration in Hartford was a contrast to the prevalent “pessimism” about immigrants. Quickly, it’s understood that this population is only given value when they show the ability to rapidly assimilate, and, the article quickly veers antisemitic, though it is unclear if those remarks belong to the unnamed reporter or if that Courant employee was paraphrasing Weaver. Either way, this passage gives a taste of what praise for Hartford’s school system looked like at that moment in time:

Give yourself a scream break.

There’s a lot to object to in that passage, and I don’t want to belabor it, but will add that while absolutely there was an awareness of tenement conditions being unhealthy — largely because of overcrowding — the solution always seemed to be along the lines of removing the buildings, and not in finding ways to make it so people did not have to live in cramped spaces. How can this be read other than if you take away the housing, then they will move on and become someone else’s concern?

It’s not as simple as building just any kind of new buildings. From then until today, we’ve had lots of new housing in Hartford, yet what was exposed a century later in the pre-vaccine Covid pandemic was how city residents remained vulnerable to illness because they were (1) living in cramped spaces where quarantining from housemates was not possible, and (2) often doing work that could not be done remotely. Meanwhile, the wealthy were off buying second homes in increasingly remote locations. Give yourself another scream break.

Even in 1911, however, getting people to accept more tenement housing development was a task. One article from May of that year pointed out how most new housing in Hartford was for the wealthy, while what was needed was more affordable residences. Was that being planned for any of the “land” gained in river harm? If so, it was not specifically named.

Back to December 20, 1911:

![]()

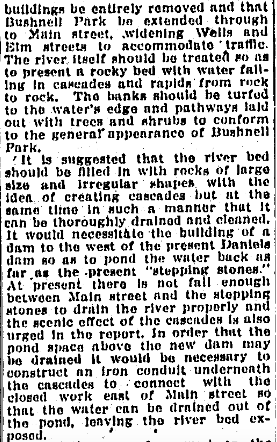

“From the west side of Main Street to a point 300 feet west of the Daniels dam the committee suggests the buildings be entirely removed and that Bushnell Park be extended through to Main Street, widening Wells and Elm Streets to acommodate traffic. The river itself should be treated as as to present a rocky bed with water falling in cascades and rapids from rock to rock. The banks should be turfed to the water’s edge and pathways laid out with trees and shrubs to conform to the general appearance of Bushnell Park.”

“It is suggested that the river bed should be filled with rocks of large size and irregular shapes with the idea of creating cascades but at the same time in such a manner that it can be thoroughly drained and cleaned. It would necessitate the building of a dam to the west of the present Daniels dam so as to pond the water back as far as the present ‘stepping stones.’ At present there is not fall enough between Main Street and the stepping stones to drain the river properly and the scenic effect of the cascades is also urged in the report. In order that the pond space above the new dam may be drained it would be necessary to construct an iron conduit underneat the cascades to connect with the closed work east of Main Street so that the water can be drained out of the pond, leaving the river bed exposed.”

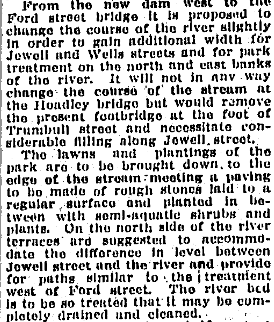

“From the new dam west to the Ford Street bridge it is proposed to change the course of the river slightly in order to gain additional width for Jewell and Wells Streets and for park treatment on the north and east banks of the river. It will not in any way change the course of the stream at the Hoadley bridge would would remove the present footbridge at the foot of Trumbull Street and necessitate considerable filling along Jewell Street.”

“The lawns and plantings of the park are to be brought down to the edge of the stream meeting a paving to be made of rough stones laid to a regular surface and planted in between with semi-aquatic shrubs and plants. On the north side of the river terraces are suggested to accomodate the difference in level between Jewell Street and the river and provide for paths similar to the treatment west of Ford Street. The river bed is to be so treated that it may be completely drained and cleaned.”

It’s perverse, really. You can hear how the decision-makers of this time regarded nature as a plaything that they could do with as they chose, so long as it did not offend their aesthetic sensibilities. As long as they could afford it.

Which they really could not at this time.

When could they? When suddenly there was federal money available for flood projects.

In 1911, their desire to mangle the Park River had nothing to do with flood prevention; it did when it meant getting money for the project.

Our problem has always come when we have mistakenly believed in the old myth about humans having dominion over nature. We’ve buried and channelized much of the Park River, buried much of Gully Brook and Cemetery Brook. We’d installed a giant dike system. We’ve done extensive sewer projects.

And still, it floods.

Because we haven’t learned humilty or how to live lightly. Because we don’t understand math and science. Because we keep doing the same thing over and over — adding more concrete — and expecting different results. Because we continue to lie about the real reason for why the Park River was buried.

We need to be honest about our past, and that means we need to learn it — not simply accept at face value what is said confidently on Hartford history nostalgia websites. We need to hire creative thinkers who understand science. We need to look at how we choose to live as individuals and make better decisions when we are able to do so.

Photo: View of the Connecticut River, still flooded in parts, as of late January 2024.

Climate Possibilities is a series about climate mitigation, along with resilience, resistance, and restoration. It’s about human habitat preservation. It’s about loving nature and planet Earth, and demanding the kind of change that gives future generations the opportunity for vibrant lives. Doomers will be eaten alive, figuratively. All photographs are taken in Hartford, Connecticut unless stated otherwise.

Donna Fleischer

Truth based on facts and documented opinions. Refreshing.