Occasionally, artwork makes a lasting impression.

In the summer of 2015, I was staying at a cabin in Pittsburg, New Hampshire. Most people I’ve spoken to in Connecticut — at least the ones I’m not related to — don’t seem to know there’s New Hampshire north of Mt. Washington.

At check in, if I recall, the office manager let me know about hiking on and near the property, where I could gather all the raspberries I wanted, and that there was an art installation on one of the trails.

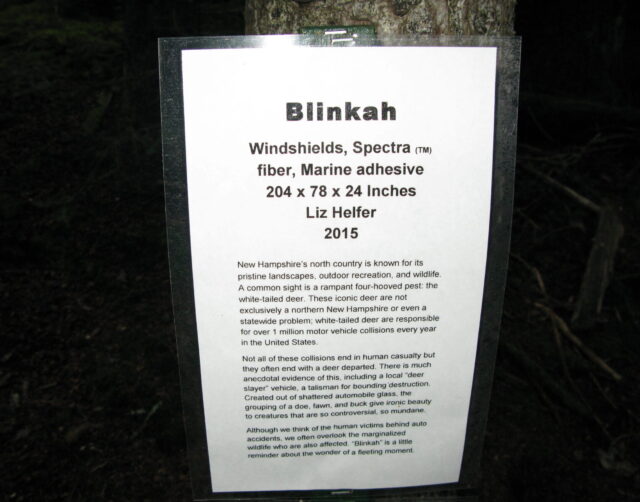

People often think of deer as not belonging in roadways, so seeing deer-shaped objects constructed from windshield glass in the woods was another flavor of the unexpected. It was also chilling. I thought about it for years after, and then recently found that I had saved the not-so-great photos I’d taken. (There are crisper photos on the artist’s website)

There’s skill involved, but this is art that makes one think, and the artist, Liz Helfer, has plenty more that does just this.

“Blinkah” was placed on a wooded trail in the last town before Canada, population 800. If you’re visiting, it’s likely you are there for one or more of these reasons: hunting, fishing, paddling, riding ATVs, snowmobiling, hiking, or looking for moose. Or, you’re passing through to experience La Côte Magnétique in Chartierville, Québec. This is not a place renowned for galleries and cafes.

If you want art to be seen here, you put it trailside by a campground that’s in view of First Connecticut Lake. Make it something that people being curious may just . . . find.

You might say that it comes out of nowhere.

Unlike crashes involving pedestrians/cyclists, deer do often come out of nowhere, springing into roadways from the vegetation and brush.

But, it was their space. They did not ask for the highways. They had no opportunity to attend soul-numbing public hearings about planned developments. They asked for none of this, and benefit from none of this.

As part of NautiWeek, WNPR recorded a show about diamondback terrapins. Eventually, the conversation turned to how frequently drivers strike them. A previous WNPR piece got into efforts to build culverts, requiring no behavior change of drivers.

On August 5, 2023, police pulled over a Farmington driver clocked at 110 MPH on Route 44 in West Hartford.

A year ago, in August 2022, police pulled over a driver going 95 MPH on Route 44 in West Hartford.

I see coverage of these kinds of incidents and can tell from the breathless reporting that we are expected to have a particular kind of response, one that condemns the reckless motorist. There is pretty much an annual “police are cracking down on Talcott/Avon Mountain speeders” news piece, which considering that speeding still happens, should make us question the effectiveness of this system. (Also, thanks to the Internet, we can easily see that these are recurring stories)

Five years before a notoriously horrible crash with multiple fatalities, the Courant reported on how Avon police were pulling over speeders: “The speed limit is 40 mph, but few, if any cars, drove that slowly. [An Avon officer] clocked a commuter bus coming down the mountain at 40 mph, but most cars drove past at speeds of 57, 60 and 63 mph.” That was in 2000.

Six years later, the Courant would run another such piece, noting how a driver was going 60 MPH on the Avon side. That was in the year after a truck crash killed four and injured 23 people; an American Crushing and Recycling truck had a mechanical failure — deemed to be the result of negligent maintenance — and slammed into cars and a bus at the intersection of Route 44 and Route 10 in Avon.

A major construction project on the “Talcott/Avon Mountain” section of Route 44 in Avon and West Hartford began in spring 2008. Aside from the ramp to catch vehicles with failed brakes, I’m not convinced these changes made for a safer road. On the Avon side, a median was added, but so was another lane. That lane was not a bike lane, nor was it a sidewalk. Those don’t exist on Talcott/Avon Mountain. On the West Hartford side, a painted median — so, not an actual median — was added. Curves were untightened. If you know about road design, what this tells you is that the changes enabled drivers to travel at higher rates of speed in general, and then even more so at non-peak travel times. They could have gone in the other direction — removed lanes and lowered the speed limit.

Five properties, two of which were homes, were taken for this reconstruction, specifically for the project’s most useful feature — the escape ramp. The runaway truck ramp was not even an automatic change following the 2005 crash. It only came up again after a similar crash. In this one, the driver was able to steer to avoid causing as much damage to others as possible. The truck plowed through a furniture showroom, but there were no fatalities this time, and the only injury was to the driver. This is only recent memory. There were many other truck crashes prior on Route 44, including one in 1945 when five cows being transported were killed in a crash on the West Hartford side.

Did the construction project make a difference?

In December 2020, a crash involving a truck and two other vehicles at the base of the mountain in Avon resulted in 3000 gallons of heating oil spilled and one person experiencing minor injuries. If you don’t remember this, it was probably because of the pandemic daze.

Since 2015, there have been at least 432 crashes on Talcott/Avon Mountain, 23 involving heavy trucks. Of the 432 collisions, 96 resulted in injuries and two were fatal. Both fatalities were in 2016, and both killed were 33-year old women. One, from Simsbury, was reported to be doing drugs while driving and had a blood alcohol level triple the legal limit; witnesses observed her driving aggressively and erratically before the crash, weaving into oncoming traffic. The other failed to negotiate a curve (traveling too fast for conditions) on a dark, wet, and foggy night.

By doing the math, it would seem that 336 of those crashes on a 3.2 mile stretch of road only resulted in property damage, and according to others’ narrow definitions of what can be damaged or harmed, that would be the case.

However, a closer look shows that since 2015, there were reports of 41 collisions with animals — 19 in Avon and 22 in West Hartford. Most of those crashes involved deer, but three were bears and one was a fox. Three of those indicated possible injury, but that’s a comment on what humans experienced. The data does not tell us how many of those animals were killed, how many maimed, or how many may have gotten away with minor bruising. It was not always clear if the animal was struck, or if someone crashed while swerving around one. No explanation was really provided as to how a person manages to strike a bear — something only slightly less plausible than driving into a cow. What data does not tell us are those animal strikes that went unreported, and judging by how many people evade responsibility after running down humans, it’s safe to assume that the number is high. There are motorists who, unless the damage was significant enough to report to their insurance company or caused their vehicle to require a tow, would drive off as if nothing happened.

The posted speed limit on Route 44 is 40 MPH. The road, and these vehicles, were designed to permit excessive speeds. Do not be surprised, then, when people go too fast for conditions.

Awareness signs and special paths for animals are nice, but if we aren’t redesigning roads to prioritize safety and if we aren’t requiring speed limiters on vehicles larger than scooters and bicycles, we aren’t serious about protecting animals — including people — from ourselves.

Climate Possibilities is a new series about climate mitigation, along with resilience, resistance, and restoration. It’s about human habitat preservation. It’s about loving nature and planet Earth, and demanding the kind of change that gives future generations the opportunity for vibrant lives. Doomers will be eaten alive, figuratively. All photographs are taken in Hartford, Connecticut unless stated otherwise.

Richard Nelson

Ghost like silhouettes of the dead. Smashed Windshield Glass Memorial to Departed Deer.

In Liz Helfer words, “these animals are created in response to the casual destruction of life around us.” How often do we think about all of the animals killed by vehicles in the U.S each year? Very rarely until I was introduced to this by Liz Helfer’s artwork, Blinkah on this site. I will try not to sound like a broken record here but isn’t this what art should be doing in these times as our very planet and everything on it is in the fight for life. Shouldn’t we be looking at the art of resistance against the accepted? Art that moves us from this place to a new place, art that helps us see ourselves in the world, art that tells us where we are at in relation to other living creatures rather than us just standing around discussing the talent of a person creating a happy painting that amounts to nothing more than the tastes of their bourgeois masters and handlers and simpleton tastes in art. The fiddle has its place but now is the time for the drum.

One Idea Pushes Another. Or What did you learn today?

Claire Carlson writes in her essay Wildlife Crossings an ILL-Suited Solution to Animals Killed by Vehicle Collisions: How preventing wildlife deaths means a societal shift in how we transport ourselves: “The positive impact of driving less on the rate of wildlife vehicle collisions was illustrated during the height of the pandemic stay-at-home-orders in March and April of 2020. The number of collisions in states like California, Idaho, and Maine declined by 21-58% in those two months, according to research by the Road Ecology Center. If this reduction were to have sustained through the year, it would have meant that between 5,000-13,000 large animals in these states would have avoided death by vehicle collision.”

One statement that is common in many articles stands out for me, “white tailed deer are responsible for over 1 million motor vehicle collisions every year in the United States.” West Virgina leads the 12 worst areas ranked for deer accidents. I think that statement should be written the other way around to “those who drive the weapon we know as a car are responsible for the 1 million motor vehicle collisions every year with white tail deer and many other creatures.” That way perhaps WE can do something about these deaths. We then hopefully find a new freedom here and move forward.

One solution that is stated is to drive less. Professor Fraser Shilling director of Road Ecology Cener at UC Davis has this to say, “Individually, don’t speed, but as a society, we have to find a way to drive less, like massively drive less,” said Shilling. “The best thing to do for wildlife is to find ways to support a society where driving is not essential.”

Important words by Amazon theorist Butch Lee come to mind, “Because there is no sense in fighting for freedom in general if you don’t free yourself along the way. Actually, it is the only way that it works.” Night Vision, Butch Lee

Kerri Ana Provost

Thank you!

The mitigation tunnels/bridges remind me of paper straws instead of plastic.

. . . Or, we could just not use straws unless there is an actual reason to?

. . . Or, we could only drive when absolutely necessary.

I know I’m a broken record about this, but the Car Brain episode of War on Cars has this fantastic little rant in it:

https://thewaroncars.org/2023/01/31/car-brain-with-dr-ian-walker/

I’ll sum it up, but folks should give it a listen: we hear people say they need their cars because otherwise they can’t get to work, to the grocery store. Okay, fine. If this is true, then people should be combining errands and only driving where they absolutely must. Not idling outside of schools. Not circling the block to find a “better” parking spot. I love the rant so much because the people I often hear this from are those who’d call themselves progressive urbanists. They say they want one thing, but then act in opposition to that — and not as an exception, but as their norm.

Laura Pallandre

Thanks for this website and sharing the picture of the plexiglass deer in NH – beautiful. I saw somewhere that you were doing a bookclub in September? I am poking around your website trying to find that. I will. be back, it’s very good.

Kerri Ana Provost

Thank you!

Book club:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1piAKLb5mI-ETrI77FSmbi4rCyehmy5uFsEIcnuWzFGw/edit?usp=sharing