The easternmost unit of the Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge is in Westbrook along the Menunketesuck River. These 300+ acres of forest and salt marsh serve as a rest area for migratory birds using the Atlantic Flyway, as do the other parcels in Connecticut’s only wildlife refuge. Westbrook’s Salt Meadow Unit is designated as an Important Bird Area “used by over 280 species of migrating neotropical birds during the spring and fall migrations,” and using a wildlife viewing platform, you can attempt to spy on them. The main paths are maintained well, and while I believe it is possible to get lost anywhere — I’ve tested this — you can get yourself unlost here quickly without calling for a search party.

Feel like you’re reading a lot about birds here lately? You are, and it’s intentional. Low-carbon birding is possible. Yes, even in Connecticut. To reach this location, you can bike from the Westbrook train station in under ten minutes, lock up your ride, and take out your binoculars or camera.

And if you don’t ride? There are other options.

But first, where and what the hell is Westbrook?

When I decide on a place to visit, I usually know something about it already, whether that thing is true or some marketer’s embellishment.

I might start at a town’s Wikipedia page to get an idea of the basics. Going on that alone, Westbrook seems to want to say the least possible about itself. For instance, its history is listed as a single sentence: “Westbrook was incorporated in 1840.” It feels like being outside of myself, watching as someone asks me what I do, and I say “stuff and things,” while trying to telepathically convey that the asker should turn their attention elsewhere.

With so little to go by, I could imagine different scenarios. Someone in New Haven or New London getting in a tiff with fellow residents, probably about ye olde affordable housing being built, and writing a terse letter about why they are leaving, pinning it to a hitching post or something, and then galloping away to a place nobody will have heard of, and therefore cannot find and populate.

But the imagination comes to a halt when one finds, on the official town website, that Westbrook does have a history. It was the western section of Old Saybrook before splitting off (peacefully? angrily? whatever) and becoming its own place which, disappointingly, does not have its boundaries decided by any brooks. Rather, not organically. Looks like a point where Cold Spring Brook meets Long Island Sound was chosen, and then straight lines were drawn in.

If you want to know more about the town’s actual history, a Girl Scout created three walking tours.

In January 2023, better late than never, the town registered with Sustainable CT, which means it has committed to focus on sustainability efforts (139 or Connecticut’s 169 towns have registered so far, and only two of the nine towns currently described as “climate leaders” are east of the Connecticut River). By joining the program so recently, there is nothing official and publicized yet about what actions they plan to take, but last year Westbrook joined the Pollinator Pathway program. They also expanded the town’s open space by 20% in 2022 with the purchase of one property that connects to those owned by the Essex Land Trust and another by the Westbrook Land Trust. Developers decided that something about the 130 acres near Toby Hill Road was not going to work out for their housing project, and talks about transfer began seven years before it happened. The purchase was helped along by grants from CT DEEP’s Open Space and Watershed Land Acquisition Program; the start of a brook is on this property. Nice save!

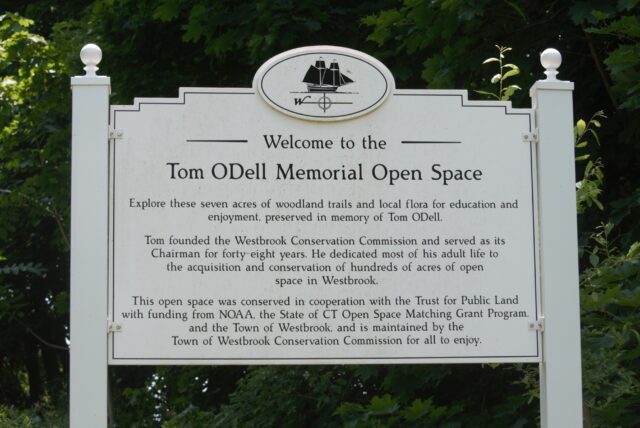

This is not the first time developers abandoned a project, causing the town to benefit. From the train station, another such space is a ten-minute walk. The Tom ODell Memorial Open Space is accessed from Route 1, between a school and post office.

There are seven trails on 6.99 acres acquired by the town in 2004, dedicated in 2021. Five of those acres were stripped of their trees in 1968, with the expectation that a housing subdivision would be erected here. By the early 1980s, this plan to build in a floodplain was officially abandoned. Now, people are attempting to undo the damage from over fifty years ago by controlling invasives, like multiflora rose, and restoring coastal forest.

The terrain is mostly flat, with some slope. If you’re looking for a mountain to climb, this is not it. Instead, you’ll get views of wildflowers and salt marsh.

This is another place to not worry so much about getting lost. It’s relatively small and bordered on the north by Route 1, south by salt marsh, west by a school, and east by homes.

Currently, it’s a smidge overgrown on some trails, but there are signs that maintenance is underway.

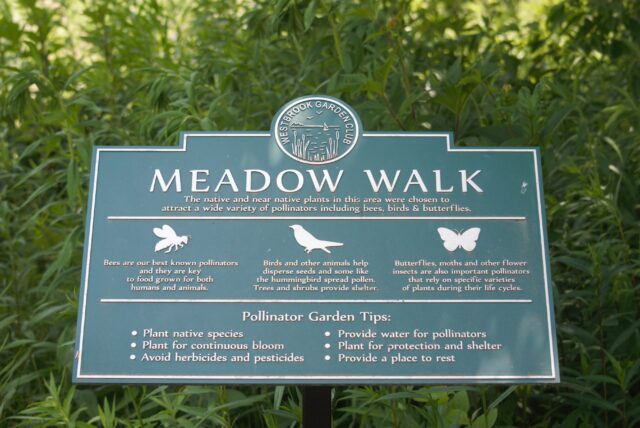

At the entrance to all this is the Meadow Walk made by the Westbrook Garden Club.

Here you’ll find native (or near native) plants that I rarely saw growing up, but are thankfully becoming more common as people realize the benefits of creating environments that support and attract pollinators.

The Meadow Walk is not a large space, but it’s one that could (and should) be replicated along roads, and even within oversized parking lots. Most, if not all, of the plants are labeled, making it easy for visitors to take note of what they like and might want to add to their own yards.

There are a few benches not so far in if you want to sit and listen to birds and watch butterflies.

Or, see a brilliant jewel-tone insect land behind you on a bench.

In the time it took for me to confirm that this was an Emerald Ash Borer, which I had not seen before and was beginning to wonder if it were mythical, the critter dashed off. Probably to go be boring somewhere.

Perhaps this was the reason for that sign:

Invasive insects and overgrown trails notwithstanding, I can’t help but like a space that greets visitors coming from the sidewalk. It’s something you notice when the norm is to stick trailheads only within parking lots.

A trip via Shore Line East would not be complete without a visit to the beach, and that is not far from the Tom ODell Memoral Open Space trails.

Salt Island Road leads to Middle Beach. Can you walk out to Salt Island from Middle Beach during low tide? What you can do and should do are different things, but consult a tide chart first as not to wind up straining local resources. However, Salt Island is open to the public, while Westbrook’s other two islands — Duck and Menunketesuck — are not, or at least, not always. Duck Island is closed to humans during nesting season (April through October) and Menunketesuck Island, part of the National Wildlife Refuge, is always off-limits to people. Those are classified as Important Bird Areas, with lots of Snowy Egrets, plus other birds that deserve to not be hassled.

If skipping the open space trails, another option is to head for Seaside Avenue and walk until you see sand. That’s 15-20 minutes from the train station, with at least half of the time spent on calmer, quieter roads than Route 1, and to be honest, this is some of the mildest section of Route 1 that I’ve spent time walking along. I’m guessing that’s because the only thing people expect to find in Westbrook are the outlets.

(P.S. If you wanted to go to the outlets, you could walk there from the train station, or hop on the 641 bus)

Use the Westbrook Station on Shore Line East.

There is some bus service, provided by River Valley Tranist/Estuary Transit District, which uses the Token Transit app.

You can get from the train station to the beaches and open space mentioned in this post on roads with sidewalks, but there is no sidewalk connecting to the Salt Meadow Unit or to many other places of interest in Westbrook; residents strongly desire more sidewalks in town, and based on this, I would expect to see access expanded in upcoming years.

Note: There are some feisty, loud birds living on the train station platform.

You may want to wear a hat.

Multi-Tool – Real Hartford

[…] reducing flash flood impacts, rain gardens help filter nasty chemicals out of the water. You know how sometimes after heavy rainstorms we hear about various beaches and swimming holes […]