Elitist attitudes over who may use public space were not born yesterday.

And it does not get much more stuck up than deciding who deserves to sit and where and for how long. With the advent of political correctness, people now know that disparaging the poor is a bad look, but that does not mean the end result is any different. Today, some property owners and cities make use of hostile architecture — like benches with “armrests” in the middle — which discourages the L-word (lingering! loafing! loitering!) or as is often the case, they provide few-to-no amenities for people using outdoor spaces.

Hartford has been no exception.

It’s not that we have no benches in Hartford. We generally do not have enough in places where people want to sit.

If you look at the park over I-84 — not the skatepark segment, but the two slivers on either side of it on Trumbull Street and Main Street — you’ll find lots of seating, which is almost never used. Why would it be? The space is unpleasant and not a bus stop. One or two benches in either part would more than suffice. But then there is absolutely no public seating on the block of Main Street between Talcott and Temple– the location of a community college and major bus stop.

On Asylum Avenue, there are no benches, or bus shelters, between Prospect Avenue and Asylum Place. That’s 1.5 miles. So far, there is nothing in the so-called Asylum Avenue “road diet” that indicates the addition of these features. You would think that St. Francis/, Classical Magnet, and West Middle, or any of the churches, at least would act like they were part of the community and provide something near the road where people wait, often while traveling to and from their facilities.

There is no seating outside the exceptionally busy clinic next to Buckingham Square Park. That’s a choice. A crummy one. It’s also a well-used bus stop. What is gained by not giving a little comfort and dignity to those needing services there? The emphasis is on “little,” as benches are rarely so comfortable that anyone would want to linger for long stretches of time. The next closest bench, heading north, on that side of the street is five blocks away at a major bus stop.

There are many, many streets and parks in Hartford that lack basic seating, but readers can go out and do the legwork themselves. Many already know what exists, or doesn’t.

Parking spaces only serve as babysitting for private property that requires a level of wealth or willingness to get into debt, yet parking is treated by many as sacred. Regardless of income level, we all have bottoms. Imagine if we were as aggressively vocal about having a place to rest our haunches as people are about parking.

Hartford’s bench inadequacy is not unusual. To paraphrase an extensive article about bus stop conditions in Connecticut: most of this infrastructure is horseshit.

There is a group actively working to make this less true, but first, a history lesson, because just as benches do not magically appear, they also do not magically disappear.

In 1930, Rev. Warren S. Archibald of South Congregational Church complained, publicly, about the benches in Buckingham Square Park. He referred to it as a “haven for loiterers,” and was seemingly quoted by the Hartford Courant as saying “the animate and inanimate aspects of the park do not make suitable surroundings for the church” across the street. Some pushed back against this uncharitable viewpoint, including the Hartford Central Labor Union, but the paper barely covered that perspective, choosing instead to focus on how “one resident declared that the loafers prefer Buckingham Square to Colt or Bushnell parks because of its close proximity to John Street, which he characterized as the ‘wholesale hooch district.'”

The benches were removed and judging from later complaints, it seemed that the “loafers,” as the paper called them, had moved on to Bushnell Park. Two years later, they did run a lengthy letter to the editor calling out the church: “such an attitude, it seems to me, is entirely out of accord, not only with the teachings of Christ, but also with true Christian living.” The writer continued: “When any member of the clerical fraternity feels it beneath his dignity to exemplify the spirit of his mater in this regard, well, I just wonder how he reconciles his attitude with his preachment of ‘brotherly love.'”

We’re going on almost a century without benches in that location.

If you’ve been in Hartford for more than a minute, you’ve heard of George A. Parker, somehow. The name probably floats around as a mystery in your mind, and then you might recall that Parker Memorial Community Center was named after him, and that tidbit is probably good enough. . . but wait, there’s more!

Parker moved to Hartford to serve as superintendent of Keney Park in 1906, back when that was a thing, and unlike some who show up here to extract wealth and then leave, he spent the last two decades of his life serving the city. In his first year here, there was a push to remove benches from the north side of City Hall for reasons that the Hartford Courant reported as “a nuisance in that they were occupied at all hours of the day by ‘bums,’ for whose use the benches were not at all intended.”

Without commenting on every single thing Parker said or did in his lifetime, he had at least two mic drop moments involving benches, and this was the first one.

Having installed those benches, he challenged this snobbery coming from a City commissioner and spent 57 hours observing who was using these seats and how. What he determined was that over that time, 9418 people used benches and less than 1% of them were who people of that time called “bums.” Parker said that about “600 women, forty of them with babies in their arms, use these benches daily […] and they should certainly have as much consideration taken for their comfort.” He noted that very few people spent longer than an hour at a time at these benches except for in the evening, when demand would be decreased. The benches stayed.

Maybe his name drew him to believe in people’s right to park their butts down without excessive disturbance. The next year, there was discussion of returning benches to Tunnel Park where they had been previously removed because, as the paper put it, “they had proven a nuisance.” I won’t name names here, but literally two neighbors were reported as griping about the benches. It felt a lot like how today you’ll get these up and coming professionals who move into buildings downtown and then be mad because the bar they live above is making noise like a bar.

There was no immediate follow up on what happened there, but in 1911, the controversy arose again. Keep in mind, around this time people were also complaining about “obscenity” and noise from baseball games, restricting them in Pope Park from 12-1 PM only.

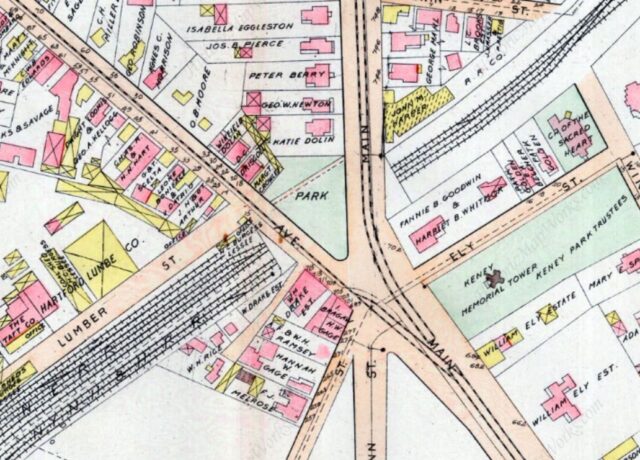

But we’re not here for the sportsball. This is about the right to sit still. Tunnel Park is the small patch of land where Albany Avenue and Main Street come together. The 1896 map below shows what area looked like before park narrowed and cut into by area roads.

If you’re trying to get a visual, think more like Barnard Park and less like Elizabeth Park, both in scale and types of use. So, Parker had been in Hartford for a few years now, and this is pure speculation, but had probably had his fill of people with their prissy attitudes about how public space should be used. Even if the paper did not cover it, we can guess that the neighbors who were scandalized by people being loud and drinking in the tiny park continued their quest for the public space abutting their properties to serve as a default extension of their private property.

At this point in the story, it would seem like our hero had two choices: find some way, probably using polite language and an attempt to empathize, to tell residents that the benches were staying, or, appease them by removing the benches.

But, there are never only two options. It’s here when, according to the paper, Parker had the parks department drop off seventy benches at Tunnel Park. As he told the paper later, the result: “No hoboes, no disorder.” Whether his aim was to truly reduce park use by certain populations or a way to smooth things over with the whiners is unclear, but he did explain that more “seats and lights in a park do a better policing than any police force would do.”

Seventy benches, y’all.

What we know about George A. Parker is that he took recreation seriously, and there is no other way to interpret showing up to a very small park with a very large number of benches than him telling NIMBYs of yore to take a seat.

You might think this was the end of it, but you would be wrong. In 1927, twenty years after neighbors got press for opposing the reinstallation of benches, one of the same who had complained decades before again voiced his distaste for people existing in public space.

The timing was no coincidence.

The Courant published, one year to the day after Parker’s death, an article going after activities in Tunnel Park: “Recent discovery of 17 empty [illegible] bottles” under the hedge on a neighbor’s property was cited as “ample and sufficient reason for the park board to order the removal of all benches from Tunnel Park.”

With the “father of Hartford’s recreation program,” who was regarded in his obituary as a “visionary,” out of the way, the great unseating of the masses could resume. Not all seats were disappeared, and In the decades that followed, the paper would publish the names of those who were arrested in Hartford for sleeping on park benches. Because getting some beauty rest is a crime!

This is just a glimpse at one of the ways that those with mobility challenges, or who are simply tired, have been deprived places to sit while waiting for a ride. And it’s an issue that does not get nearly enough attention because in a society that has centered the automobile, where decision-makers almost always move around in private vehicles, there is little consideration given to those who are not traveling via metal cage containing an entire living room worth of furniture. They don’t have to think about where they might sit, and are not overly concerned with how the elderly, those with disabilities, and those who simply have long waits for the bus make do.

That brings us to now, where most bus stops in Connecticut are woefully deficient — no seats, no shelters, just a post with a sign — if that — naming it as a bus stop.

A growing group of doers are changing this.

So far, Connecticut Urbanists have installed a few benches in Hartford and East Hartford at bus stops.

Spencer Early of Connecticut Urbanists says they “choose high frequency corridors and pick stops in dense areas that currently lack seating and have room for a bench.”

In the vein of “it shouldn’t have to happen to you to matter to you,” there’s no story of Early waiting for hours in the rain or being personally incapacitated. He simply observed the landscape. “I frequently see people waiting

for a bus and there is no bench,” he said, “particularly on Main Street,” north of downtown.

Local response to this action has included requests, with the suggestion of a bench on Ashley Street near Sigourney Square Park. Connecticut Urbanists say they are hoping to install one there this coming spring. That’s not all they have in store. Despite the size of the group — just a handful of volunteers right now — they are ambitiously aiming to add seven new benches by the end of March. Early says that they “plan on continuing after that, but it’s hard to predict exactly [how] many benches we will do.”

What they can accomplish is determined by time, energy, and funding. Early says they are “currently focusing on growing our Hartford membership and expanding into the Danbury and New Haven areas, but anyone in Connecticut is welcome to join.”

Those who can donate time and labor have an opportunity to pitch in on February 11, 2023, when the group meets in Colt Park to assemble benches possibly destined for bus stops at Linden Place, the area next to Buckingham Square Park, and across from Church Street. If you wanted to undo bad decisions for the past, here’s your chance! You can also throw money at the problem, if that’s more your speed.

Our current era is defined by undoing the damage caused by previous generations, from climate crisis to divisive and deadly highways to buried rivers. And now, we are reclaiming the right to sit the hell down.

Richard Nelson

Love it. Once again, you have proven that where would we be without you and your writing. I love bench sitting and it’s become more important as I have gotten older. I love bench sitting to sun myself, yeah, I am a bum, and to rest my tired feet. You know I walk places and a good sit-down and rest is divine. Long live Mr. Parker. I have always given a hearty laugh to the trials and tribulations of the comfortable class. Many, many moons ago when I left home suddenly, I slept on a bench in Central Park. In those days my only fear was that a rat would crawl up and get in my pants.

I have to ask is the Urbanists bench in the photo at a bus stop? (I believe I see a bus stop sign showing stop. If so, shouldn’t it be facing the street so one could see the bus coming. I suppose no one wants a person to come up behind them, but then a person while sitting must also be aware of drivers who love to jump their vehicle up on the sidewalk. But who is to squabble as it’s great to have a place to sit whichever way one faces.

Once again Thank you for your excellent articles as always.