If you struggle with the ability to hold many complex, and at times contradictory emotions at once, visit Quabbin Reservoir. That’ll cure you.

It’s in central Massachusetts, and despite living in Connecticut my entire life, I have never heard someone say they were vacationing there. It’s always “Going to The Cape” or “camping in the Berkshires” or “Visiting Boston.” But central Mass? What even is there?

I was curious, and considering nobody ever talks about it, I felt like this had the makings of a Covid-safe vacation. The map showed a giant expanse of green with a large body of water in the middle. Quabbin Reservoir. Maybe that’s something?

Eighteen miles long with 118 miles of shoreline, plus 63 miles of island shoreline, the Quabbin Reservoir holds a potential 412 billion gallons of drinking water. If you’re looking at this on a map and trying to make a logical guess as to what towns are supplied, you’d see that the closest ones with any sizeable population are Amherst, Northampton, and Holyoke.

But, that’s not where the water goes. Instead, it takes a 65 mile trip to serve Metro Boston. Here is one description of the path it takes:

“After entering the Quabbin Reservoir at Shaft 11A, it takes five years for Ware River water to travel around the entire Quabbin Reservoir before re-entering the Quabbin Aqueduct at Shaft 12. This extended residence time allows natural purification processes of light and mixing with the higher quality Quabbin watershed water. Entrance in the Quabbin Aqueduct

at Shaft 12 sends water eastward, by gravity, to the Wachusett Reservoir.

Before exiting at Shaft 1 into the Quinapoxet River, the water first generates electricity at the Oakdale Power Plant. This hydro-energy is sold to

the West Boylston Municipal Light Plant, earning revenue that off-sets the

costs of the DCR Watershed Management Program. In a typical season,

the amount of water transferred from Quabbin to Wachusett ranges from

50-100% of the volume of the Wachusett Reservoir. At any time of the year

approximately half of the water in the Wachusett Reservoir originated in the Quabbin Reservoir. […] Once the water enters the Cosgrove Intake in Clinton, it completes the journey east through a series of aqueducts, treatment facilities, and covered storage reservoirs managed by

the MWRA, and finally to a tap from a municipal distribution pipe. ”

That does not seem especially sustainable, does it?

You may think this was “just” a matter of installing pipes and delivering that water to eastern Massachusetts from a large lake, but 100 years ago, there was no large lake here. The 81,000 acres of reservoir and surrounding land developed slowly and then all-at-once.

The Massachusetts legislature ordered the Department of Health and the Metropolitan Water and Sewage Board to conduct a survey of potential water sources for Boston’s constant and increasing demand. In three years, they published a report of their findings and it took another two years to do a deeper investigation of the Ware and Swift River area. Legislators issued an emergency act in 1926, removing any obstacles the water commission may face in its mission to quench Boston’s thirst.

What might those obstacles have been?

Although not a bustling metropolis, this was not vacant land either. Somewhere between 2000-3500 living people and 7,613 deceased people would need to be relocated from Prescott, Dana, Greenwich, Enfield, and fragments of other towns.

The late Lois Doubleday Barnes, one of those originally from Prescott, and who was also one of the last to leave, was quoted in the Telegram & Gazette in 2000. One commonly repeated lie is that there was not much opposition to the clearance of four towns, but she said “we didn’t leave voluntarily and one of the things we’ve lost is the sense of community we had when we lived in those rural towns.” Rather, “it was an act of eminent domain that took our homes to provide water for people who lived far away.”

That was 463 occupied and 30 vacant homes, along with fourteen mills. That was fourteen railroad stations and freight houses, and 31.5 miles of railroad. That’s 242 miles of road. Thirteen schools and six churches. Stonewalls. Cellar holes. Trees were clear cut and burned. The remains and stones in 34 cemeteries; most would be moved to Quabbin Park Cemetery, an 82 acre parcel south of Route 9, though some families chose to move their loved ones’ graves elsewhere.

The Christian Science Monitor reported that a “man from Dana stayed on past the [eviction] deadline and woke one morning to find workers on the roof of his barn, beginning to tear it down. He went out and took away their ladder.”

Beyond the rebellion of a Yankee farmer, there was organized, but ultimately ineffective, opposition from the State of Connecticut. In 1930, Connecticut made the claim that the Quabbin Reservoir was simply not necessary and that the “diversion” of the tributaries Ware and Swift Rivers from the Connecticut River would cause damage downstream to shad, agriculture, and navigation.

The word “diversion” has been placed in quotes because from here on out, every time that phrase is quoted from an old newspaper article, or even a newer source, I will replace it with more accurate and less euphemistic language.

In 1931, a report in The Hartford Courant described the outcome of that lawsuit: “The Supreme Court finds, in substance, that the needs of greater Boston for an ample supply of wholesome water for drinking and other domestic purposes are paramount to any uses that Connecticut now makes or is likely to make of the river which bears her name.”

So the farming towns settled in the 1700s disincorporated at midnight on April 27, 1938. There was a Farewell Ball in a town hall. To this day, there are Tuesday Tea gatherings– monthly socials for former residents, those with connections to the area, and the curious. But aside from a portion of Dana — the Dana Common — those towns have since been covered in up to 150 feet of water.

Don’t think that the court case held up demolition and construction. It hadn’t.

In 1926 and 1927, the Ware River Act and Swift River Act, respectively, appropriated money for this project, marking the official beginning of the “Ware River Diversion Project.” By 1930, the Metropolitan District Water Supply Commission (MDWSC) purchased 40,000 acres of land. The population of the four towns in 1920 was 2024; in 1930, it was 1378. It dwindled from there. By 1938, eminent domain was used to take whatever remained.

What the court case did do was provide language that we would hear again and again for years to come.

Besides the sentimental costs, there were others. There always are. Either 26 or 28 people, depending on the source you trust, were killed during construction of the reservoir.

There was the money spent — during the Great Depression. $9.6 million to acquire real estate (people’s homes, people’s buildings, people’s land), $1.39 million for relocation (uprooting people’s families so they could reestablish elsewhere). Those are the prices for the 1920s and 1930s. Find an inflation calculator to grasp what this would be today. This does not include cost of construction materials or wages or transportation.

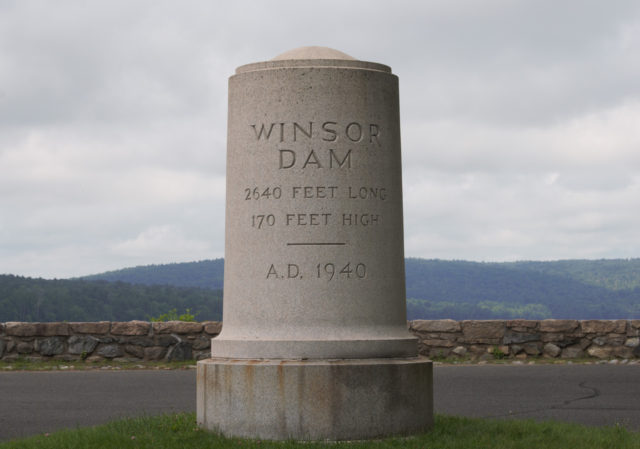

The Winsor Dam — at half a mile long — was completed in 1939; it would take another seven years for the reservoir to completely fill.

It’s a beautiful backdrop for a bitter story, until you recall that of course, this was not the first time people had been uprooted here or anywhere. Puppyville, Bobbinville, and the many other villages had gone by other names, and its current nomenclature points to that. What was one of the largest artificial reservoirs in the world when constructed was named Quabbin (Qaben), after the Nipmuc word for “meeting of many waters.”

The Nipmuc Nation today has around 600 members, and between the disease, praying towns, war, and forcible removal, know something about displacement and disruption.

Since 4000 B.C.E., the Nipmuc lived in the region. The land between Springfield and Northfield, they used for seasonal hunting. There are around 50 pre-European contact sites on Quabbin Reservoir land.

When the settlers moved in to farm, manufacture hats, and quarry soapstone, the colonists were not doing this on land that nobody was using yet.

There is a question that should be asked over and over: why?

Lois Doubleday Barnes answered this without mincing her words in 1997: “The Swift River Valley was chosen by the state, because at the time it represented an easily exploited resource.”

Displacement of indigenous. Displacement of settlers. Displacement of water.

The displacement of water was made possible by a particular worldview. Water was (and is) seen as a commodity.

This was obvious in the aforementioned Supreme Court ruling, along with subsequent attempts to steal force more water from its natural path.

In 1969, following the first Earth Day, a potential plan to manipulate what was deemed “excess water” revealed the need for both regionalism and a reckoning with how we perceive the natural world. The Hartford Courant printed a story using this headline: “Siphoning Water Into Reservoir Should Have Little Effect On River Flow.” Although the Ware and Swift Rivers were already dammed, preventing those waters from entering the Connecticut River, this new plan would have meant preventing Connecticut River water from reaching Long Island Sound. At this time, planners wanted 325 million gallons of water from the Connecticut each day. This first proposal was killed in the Massachusetts House, but it was not by far the end of scheming around water by whomever felt entitled to it.

They were back at it in 1972, with talk of this theft at Northfield, Massachusetts. The would-be thieves promised to be extra careful to avoid radioactive contamination that could occur from the newly opened nuclear power plant in Vernon, Vermont (1972-2014, R.I.P.), less than ten miles upstream.

This time, dissent would be louder. The Connecticut Forest and Park Association was among the first to oppose the attempt at stealing water. The Connecticut River Watershed Council (now Connecticut River Conservancy) called this plan a power grab by Metro Boston. The Hartford Courant in 1976 reported that the “engineers corps thinks Connecticut is making much ado about nothing,” while noting how one of the engineers who helped devise this plan said water temperatures in the river would rise from 0.6 to two degrees because of man’s interference with the water’s path. Not this nor any other news piece from the time that I could find explained how that rise in water temperature would impact the ecosystem, though 45 years later, we should all be well-versed in what the effects are.

The MDC (of Connecticut) was also opposed to the Massachusetts plan, but only because they viewed “the river as a possible new source for [Metro Hartford drinking] water sometime after the year 2000.” They, too, had commodified nature.

A group of people representing each state within the Connecticut River watershed — New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut — made suggestions in 1978. Studying alternatives to so-called “diversion” — (such as exploring underground watersheds) and the creation of a “meaningful water conservation plan adopted by Boston in advance of” any construction, as there were water main leaks responsible for some 68 million gallons of water to be wasted daily.

The amount wasted daily was close to the amount that they were seeking to gain during this round of river modification.

The opposition argued that stealing from the Connecticut River would reduce the water quality of Quabbin Reservoir. There was worry about lamprey eels entering the reservoir, which would in turn deplete the fish supply. Then, there was the concern that this was less about securing potable water and more about providing for industrial uses.

Lawmakers, in 1978, said this should be a last resort option — piping water from the Connecticut River to Boston. The following year, Ellsworth Grant — former mayor of West Hartford and a board member of the Connecticut River Watershed Council — published a piece in the Courant bringing attention to the issue: “an environmental impact study is now in progress to determine what would happen to the river’s ecology if 72 million gallons per day were withdrawn to satisfy Eastern Massachusetts.” Later that year, the Army Corps of Engineers, which helped to design the plan, withdrew its support of it, based on objections from Connecticut. Allowing any to be pumped out would set a bad precedent.

The nonsense popped up again in 1985 when one of nine possible plans to sate Boston included robbing the Connecticut River of 450 million gallons of water daily. Joseph Lieberman, then state Attorney General, vowed to take it to the U.S. Supreme Court to block this action, if necessary.

None of these plans — from the creation of Quabbin Reservoir and others, to the failed plans — asked the right question: does any area have the right to grow beyond what it can reasonably support itself on from within its own region? Why were there no maximums on housing in Greater Boston, or on any other area that had endangered or depleted its own resources? This feels like the most obvious measure, yet one that would not be taken because of the mindset of entitlement, of taking and taking and taking.

This is not a healthy relationship. There’s no reciprocity. It’s a gross assumption that the water, the land, the air — all of it — are there for humans to exploit however we see fit.

What we see having happened with water in central Massachusetts is not unique. Its Winsor Dam is named after Frank E. Winsor, a chief engineer with the Metropolitan Water District from 1926-1939. He was also responsible for the Scituate Reservoir in Rhode Island, which is the largest inland water body in that state. The situation with Scituate was similar: to obtain its 23.1 square miles for water that would be sent to Providence, 11,195 buildings were demolished. That included 375 homes and 30 dairy farms. There were reportedly suicides. This practice of going after those who could resist the least and taking their possessions, so that those in power could access the resources elsewhere, is a pattern.

Progress can be slow. We can see it in the “water bans” of the late 80s, when the Boston area was given modest restrictions, like not watering lawns in the heat of the day. Some of the conservation measures seem quaint, in the way efforts to avoid plastic straws surely will in a few decades — serving scotch without water is nice, but that’s just not where most of the wastefulness was happening.

Rather than restricting urban growth, this time there were development restrictions around the Quabbin and Wachusett Reservoirs, to preserve the health of those watersheds. A step, but hardly enough.

My favorite change was seeing someone get pissed off enough to suggest dividing Massachusetts in two — letting eastern Massachusetts become its own state. Whether or not this was a serious suggestion, the sentiment behind it is unmissable: nobody should feel entitled to anyone else’s resources.

With all of that said, there are worse things that four razed towns could be replaced by. It’s not like all these folks were evicted to make room for a highway and a soulless elevated concrete plaza.

If you knew none of the history of Quabbin or the battles over land and water, you could simply look at the reservoir and breathe it all in.

Bald eagles were re-introduced here in the 1980s and now, depending on the year, 41-to-97% of eagles seen in Massachusetts are viewed in Quabbin Reservoir. On average, there are sixteen nesting eagle pairs each year at Quabbin.

Loons, gone from the area for a century, returned to Massachusetts in 1975 — specifically to Quabbin Reservoir, where they would begin breeding.

The forest is home to black bear, moose, deer, bobcat, coyote, mink, shrew, lemmings, and plenty more.

Change, however, threatens Quabbin. It threatens every place in a way that is less deniable today than five or ten years ago. While the coast is getting nailed with revved up storms, climate change makes its mark differently inland.

The reservoir, which has an historic average of 58 days of being frozen solid, has only managed to do the same for 20, on average in more recent years; since 2015, though, there has not been a winter in which the entire lake froze.

The Q2W Forest Legacy, a conservation effort focused on conserving a 25 mile corridor between Quabbin and Wachusett Reservoirs, is one way to make this region more resilient. We are seeing more strategic forest management, recognizing how diversity of species improves the overall health of the ecosystem. An impressive 8.2 million tree seedlings were planted at Quabbin between 1936-1946, but the vast majority were red pines and overcrowding became an issue. Then, there was disease. Replacing red pines with white pines and hardwood trees makes for a healthier forest.

Preserving habitat for wildlife and creating a buffer around the reservoir to ensure high quality is great, but the forest conservation is right on time when it comes to carbon sequestration. Now, all we need to do is reforest more spaces.

Between 1958-2012, the Northeast has experienced a 71% increase in precipitation during what are dubbed “very heavy precipitation events.” Rather than blaming rivers for flooding, we now have clear cause and effect showing us how it’s the impermeable surfaces giving rain and snow limited places to go. This underlines the importance of having minimally paved, minimally “developed” areas.

Meanwhile, pollinator gardens are being added to Quabbin Park. Many are waking up to the fact that the standard grass lawn with introduced ornamental plants creates a relative dead zone. Native vegetation, however, attracts bees, birds, and butterflies — giving them the food they prefer and places to live. Already, the area near the visitor parking lot has been transformed, and there are plans for switching mowing procedures near and administration building and in a few other lawn areas.

Today, the ecological benefits of Quabbin make the eviction history seem, while not justified at the time, forgivable. When we look at other places where people have been removed, where the land has been damaged, we should be asking ourselves how we can make something better from what was a mistake.

TO VISIT

There are several entry points to Quabbin Reservoir, but to access Quabbin Park, use 100 Winsor Dam Road, Belchertown, MA in GPS. The park/reservoir is open year-round during daylight hours, but check the website first in case of temporary/emergency closures.

There are lots of restrictions. Do not bring your noisy, annoying drones up in here! No dogs or other domestic animals. No booze. No pooping except in the area designated for this. No camping. No touching of the water. No taking of things, historic or natural. No, not even if it’s the cutest rock you’ve ever seen. No littering.

Kelly

What a great read – thank you! We hear so much about water and resource grabs out West, it’s easy to miss it happened (is happening?) right in our own backyard.