Preventing crashes is preferable to dumping all our energy into punishment, but let’s pause to think about the justice aspect of traffic injuries and fatalities.

On April 10, when Isaac Alvarez’s body was found in the grass along Albany Avenue in West Hartford, the town police posted on its social media only an alert that the road was closed for an investigation.

There was nothing to follow from them, except an announcement that Albany Avenue had re-opened.

There were no subsequent posts asking the public for information. There was no acknowledgement that a person had been killed in the area. The very next post, a few days later, was this:

Is a thwarted mugging more FB-worthy than a deadly hit-and-run with the driver still at large? The posts, or lack of, read as if this young man’s death meant nothing more than an inconvenience to motorists who would be detoured for a few hours.

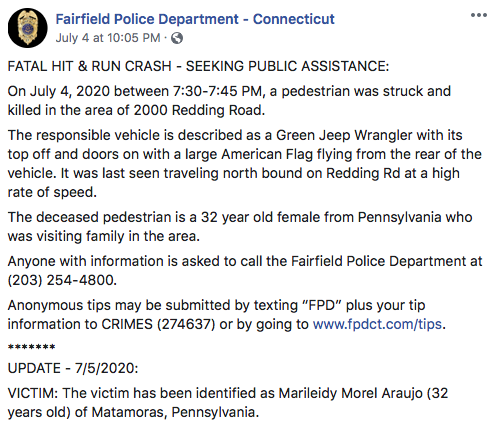

Compare that to what followed the death of Marileidy Morel Araujo in Fairfield on July 4, 2020. Within hours of that crash, Fairfield’s police posted this on social media:

Over the next few days, they posted updates about the suspect vehicle:

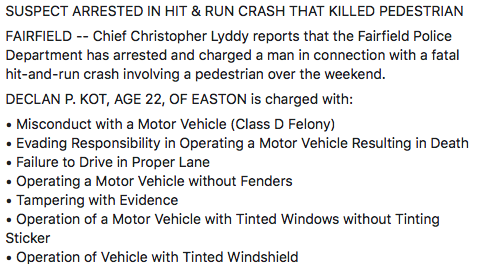

The outcome: police received hundreds of tips from the public. The community wanted justice for the victim. Declan Kot, a firefighter in Easton, was arrested four days after the incident. The cops posted about this too:

There have been questions from the public about what took so long for him to be arrested, with them wondering if his family’s connections and his status as a volunteer firefighter had anything to do with that. There were accusations of officials delaying arrest because being under the influence would mean a vehicular manslaughter charge instead of misconduct with a motor vehicle.

While I won’t argue the possibility that Kot’s privilege has served him one way or the other, as someone who religiously reads about every pedestrian fatality in the state, four days is an exceptionally fast response. West Hartford’s police essentially ignored the death of Isaac Alvarez by not asking for tips on the PD social media and took three months to arrest Sharon Esson, and that was only because she turned herself in; she has been released on a promise to appear in court in August, and there is apparently no stipulation that she not drive in the meantime. The police knew who was responsible much sooner than that: the vehicle and driver description were included in the UConn Crash Repository within weeks of the collision. The general public, who does not scour databases, would be left with the impression that her identity was only known to police at the beginning of July.

Over in Waterbury on June 5, Serenity (age seven) was outside with her mother, watching fireworks, when they and another person were hurt in a domino effect car crash. The news reports say that witnesses chased after driver Luis Loja and convinced him to return to the scene. The funeral fundraiser page, however, states: “The man then tried to flee from the scene but was later returned by two other pedestrians. Emergency services were called and the man was arrested and Yolanda and her daughter Serenity were rushed to the hospital in critical condition.” Serenity died from her injuries.

Because bystanders took action immediately, police were able to charge Luis Loja with operation of a motor vehicle under the influence, second-degree manslaughter with a motor vehicle, second-degree assault with a motor vehicle, evading responsibility, operation of an uninsured motor vehicle, improper use of registration plate, operation of motor vehicle without a license, operation of unregistered motor vehicle, and failure to drive in proper lane. None of that returns Serenity to life, but it means he may face consequences for his actions.

It’s more than how police departments use their social media though. It’s the whole package. What is the culture of a police department? What do their actions say about their values, or to put it another way, are they living up to their duty to protect and to serve.

As we have the conversation about defunding the police, some claim that police will not be able to do their jobs and we will be less safe if their budgets get trimmed significantly. Others have noticed police deliberately doing less work since this debate began — essentially striking without calling it a strike. I would argue that police have not been preventing crime on the level expected of them before talks of defunding became mainstream, and one clear place to look is at how Hartford’s force, as an example, has largely ignored moving violations and has acted in ways that suggest they do not take seriously their role in preventing traffic injuries and deaths.

Looking at Hartford’s database, there are only three reports of the Hartford Police Department dealing with speeding incidents in 2020, year-to-date. “But 2020 is a special year” you say. Yes. Yes, it is. There have been reports nationwide showing that speeding has actually increased during the pandemic. Regardless, there were only 14 reports of police intervening for speeding in 2019, 14 in 2018, and four in 2017. No year in recent memory shows the data one would hope for given the frequency of excessive speeding on city streets where people are regularly walking and biking. In 2020, year-to-date, police have done slightly better when it comes to reckless driving, but even that only accounted for around 20 reports, unless you include those connected with crashes. (If they are handling more speeding and reckless driving cases but not doing the paperwork, that’s a separate issue.)

Refusing to deal with moving violations (speeding, blowing red lights, driving erratically) suggests we can replace many officers with technology, giving speed and red light cameras the job that these humans are opting to not do. Enforcement cameras reduce the number of more serious crashes, and as a bonus, automated systems reduce interactions between police and civilians.

In Hartford, several recent headlines bring into question what our public servants are doing in their taxpayer-funded work. In one case, an officer failed to investigate a collision (with another vehicle) in a parking lot, even though he had the license plate number. You would think that if police want to maintain their funding, they would continue to do the job for which they were hired. (If anyone dares claim they are too busy to enforce the law, I can direct you to a few places where cops hang out in their cars for hours at a time, doing who knows what while serious traffic violations occur directly in front of them)

In another case, the police chief crashed a city-issued vehicle into a guardrail near the Chester-Haddam line. This caused several thousand dollars’ worth of damage to the Chevy Tahoe. He did not keep the crash a secret, yet he did not report it to the local or state police either. Chief Thody admitted to unsafe behavior by reaching for his cell phone while operating the large vehicle, but even that story has been inconsistent and there was a 911 call reporting his vehicle speeding and driving erratically for miles. He was on his way back to Hartford due to one of the Black Lives Matter protests, which was peaceful and non-violent, with no suggestion that it was pressing for the chief to arrive promptly.

Thankfully, those two incidents only involved property damage. Still, this tells us something about how traffic enforcement is treated by Hartford’s police department — it’s ignored when inconvenient.

Hartford is not unique. The proof is seen in the reports of pedestrian crashes. While it may take time and crash reconstruction to determine some details surrounding each case — driver’s impairment or distraction, speed, degree of reckless driving — what can be applied in the majority of pedestrian fatalities is the Vulnerable User Law which states that “Any person operating a motor vehicle on a public way who fails to exercise reasonable care and causes the serious physical injury or death of a vulnerable user of a public way, provided such vulnerable user has shown reasonable care in such user’s use of the public way, shall be fined not more than one thousand dollars.” Vulnerable users include pedestrians, highway workers, cyclists, those riding or driving animals, those using skateboards, a person with impaired vision, a person using a mobility device, and anyone on a tractor.

Marileidy Morel and Serenity Perez were not the only vulnerable users who were victims of vehicular violence in Connecticut last month.

Patricia Stephenson, 78 of Bridgeport, was crossing the street there when struck and killed by a speeding motorcycle; its operator was injured, but there has been no follow up on if he has been charged with anything. Police statewide seem uninterested in applying the Vulnerable User Law, which has been on the books since 2014.

Milton Williams, 53 of New Haven, was crossing the street by the New Haven Green near the library when a motorist struck and killed him. She remained on the scene; again, there have been no reports of charges filed against the driver. According to his obituary, “Milton held a multitude of jobs. From unloading ships, to building fireplaces, to moving furniture for friends and family members, Milton was a great asset to the New Haven community. If you needed him he was there. […] Milton never met a stranger. He left an impression with everyone he met and he will be missed terribly.”

Additionally, there were several pedestrians who were seriously injured, and whose condition is not yet known, as the media does not typically maintain interest in such stories if there is more than a week or so between the crash and a person’s death. That is why you may notice a discrepancy here between the fatalities described each month, and the total death count. So far this year, there have been at least three other fatal car-pedestrian collisions in state which are known only through a person’s obituary or a database.

In total, there were four pedestrian deaths in our state last month. There have been at least 33 pedestrian fatalities in Connecticut so far in 2020.

While this did not occur in Connecticut, it would be wrong to not mention another community member’s preventable death. Oz Griebel, a former gubernatorial candidate, among other things, died days after being struck by a vehicle while he was out for a jog in Pennsylvania. There has been shockingly little public information about the crash itself, including whether or not the driver is known or has been charged.

Chris D

Thanks for reporting and keeping up this effort, very journalistic. It’s a shame that these are always reported – if at all – as sheer accidents, doing everything short of (if not already including) victim blaming. I know many people will argue against automated law enforcement like red light cameras and such (because “freedom” ofc) but I agree we need to try more things like it because the status quo doesn’t work and is wildly inconsistent and unfair. Cities are definitely the better places to start with change but it’s such a deep rooted societal problem where nobody wants to seriously punish drivers because a) that could very easily be them and b) revoking the _privilege_ of driving, even temporarily, is a virtual social and economic death sentence (in most of the country), since society is built with cars ahead of people and with minimal serious alternatives.