That’s the word Andrew May used to describe his philosophy, and I wanted to ask if it was something contagious. To be honest, it probably should be.

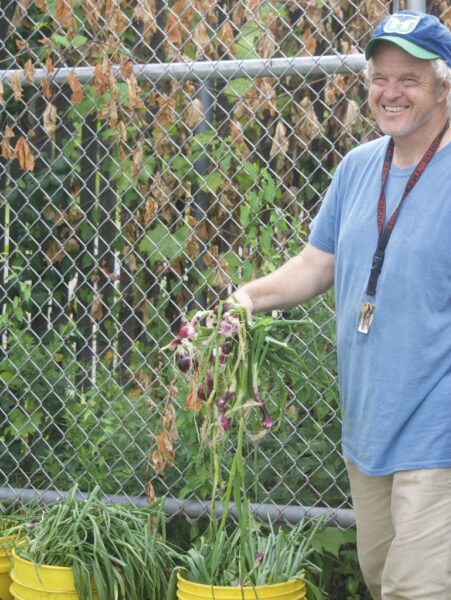

If you don’t know Andrew, do you even live in Hartford? He’s holding down plots at two KNOX community gardens — one in Frog Hollow and the other in the West End — busying himself with planting and harvesting around 200 pounds of organic Wethersfield Red onions, which he’s donating to various Greater Hartford food pantries. About 35 pounds were donated to Forge City Works to be given away at The Grocery on Broad.

In Hartford since 1995, Andrew volunteers with IRIS (Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services). He’s a rain barrel and compost bin pusher. But mostly, I know him from running into him in gardens and elsewhere throughout the city, and having rambling conversations into which he’ll casually drop quotes from Paul Farmer and John Steinbeck. And so, this will be in a non-linear form, to capture the full spirit of someone who when he spots dollar bills lying on the sidewalk, picks them up and notes that the treasure goes to charity.

This is not his first season in the community gardens, though it’d be wild if he had that kind of crop haul right out the gate. He’s gardened off and on as long as he can remember, but kicked it up in recent years, having participated in the three-year Urban Farmer program at KNOX.

The crops grown in the first year of that class were supposed to be donated to the Hartford public schools, but that was in 2020 and the pandemic threw a wrench into that plan. Another year, Andrew tried growing corn, beans, and squash together, and despite not having much luck with that, remained focused on heritage crops while adjusting to what might work out better.

He doesn’t recall what made him think that onions were the direction to move in, but that’s where he turned his attention.

We’ve had numerous conversations about the choice of Wethersfield Red onion, along with how historical accounts of the crop have ranged from whitewashed to speculative. The town to Hartford’s south was a major exporter of this crop. That part is clear. Where were they exported? Down South and to the West Indies. So, while Connecticut may not have had the scale of plantations that come to mind when we think about slavery, the state still played a supporting role in it. But, to paraphrase someone else: the onion was never the criminal.

Distributing onions through Hands on Hartford, the Wethersfield food pantry, and elsewhere is not the limit of Andrew’s imagination. He wants people to know about this project of his because he’s able to help feed people in the community through what are basically Victory Gardens. “I don’t see why we can’t get back to something like that,” he wondered out loud while we talked near the walk-in refrigerator at KNOX where his onions were stored. Through his work at Hands on Hartford, he’s aware of need in Hartford, but he’s not standing on the sidelines calling the city some kind of food desert.

Modest in his contribution, Andrew tells me that “this does more for me” than anyone else. “It’s relaxing. Good exercise.”

He has visions of witch hazel being planted on historic properties. A pollinator pathway along the Park River. He wants to see larger segments of the American lawn put to productive use. Wants to see more people involved. Paraphrasing Paul Farmer, he says, “if you’re moving the chains forward, you’re on my team.”

Climate Possibilities is a new series about climate mitigation, along with resilience, resistance, and restoration. It’s about human habitat preservation. It’s about loving nature and planet Earth, and demanding the kind of change that gives future generations the opportunity for vibrant lives. Doomers will be eaten alive, figuratively. All photographs are taken in Hartford, Connecticut unless stated otherwise.

Communitarian

That’s the word Andrew May used to describe his philosophy, and I wanted to ask if it was something contagious. To be honest, it probably should be.

If you don’t know Andrew, do you even live in Hartford? He’s holding down plots at two KNOX community gardens — one in Frog Hollow and the other in the West End — busying himself with planting and harvesting around 200 pounds of organic Wethersfield Red onions, which he’s donating to various Greater Hartford food pantries. About 35 pounds were donated to Forge City Works to be given away at The Grocery on Broad.

In Hartford since 1995, Andrew volunteers with IRIS (Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services). He’s a rain barrel and compost bin pusher. But mostly, I know him from running into him in gardens and elsewhere throughout the city, and having rambling conversations into which he’ll casually drop quotes from Paul Farmer and John Steinbeck. And so, this will be in a non-linear form, to capture the full spirit of someone who when he spots dollar bills lying on the sidewalk, picks them up and notes that the treasure goes to charity.

This is not his first season in the community gardens, though it’d be wild if he had that kind of crop haul right out the gate. He’s gardened off and on as long as he can remember, but kicked it up in recent years, having participated in the three-year Urban Farmer program at KNOX.

The crops grown in the first year of that class were supposed to be donated to the Hartford public schools, but that was in 2020 and the pandemic threw a wrench into that plan. Another year, Andrew tried growing corn, beans, and squash together, and despite not having much luck with that, remained focused on heritage crops while adjusting to what might work out better.

He doesn’t recall what made him think that onions were the direction to move in, but that’s where he turned his attention.

We’ve had numerous conversations about the choice of Wethersfield Red onion, along with how historical accounts of the crop have ranged from whitewashed to speculative. The town to Hartford’s south was a major exporter of this crop. That part is clear. Where were they exported? Down South and to the West Indies. So, while Connecticut may not have had the scale of plantations that come to mind when we think about slavery, the state still played a supporting role in it. But, to paraphrase someone else: the onion was never the criminal.

Distributing onions through Hands on Hartford, the Wethersfield food pantry, and elsewhere is not the limit of Andrew’s imagination. He wants people to know about this project of his because he’s able to help feed people in the community through what are basically Victory Gardens. “I don’t see why we can’t get back to something like that,” he wondered out loud while we talked near the walk-in refrigerator at KNOX where his onions were stored. Through his work at Hands on Hartford, he’s aware of need in Hartford, but he’s not standing on the sidelines calling the city some kind of food desert.

Modest in his contribution, Andrew tells me that “this does more for me” than anyone else. “It’s relaxing. Good exercise.”

He has visions of witch hazel being planted on historic properties. A pollinator pathway along the Park River. He wants to see larger segments of the American lawn put to productive use. Wants to see more people involved. Paraphrasing Paul Farmer, he says, “if you’re moving the chains forward, you’re on my team.”

Climate Possibilities is a new series about climate mitigation, along with resilience, resistance, and restoration. It’s about human habitat preservation. It’s about loving nature and planet Earth, and demanding the kind of change that gives future generations the opportunity for vibrant lives. Doomers will be eaten alive, figuratively. All photographs are taken in Hartford, Connecticut unless stated otherwise.

Related Posts

Leadership in Transition

Place this Place

Unhidden Gems: Ukrainian National Home