Downtown merchants, restaurants, and theaters will be offering discounts as part of this year’s Million Dollar Hartford Days. Besides the most exclusive bargains, early bird shoppers will be treated to door-to-door free bus service.

“Buses were full Tuesday¹ with early birds taking advantage of the merchants’ offer.” Through the Chamber of Commerce, retailers are paying the bus company to make transportation convenient for shoppers during Hartford Days. “Some buses arriving at the downtown starting lane² during the mid-morning were filled to standing-room only.”

The coordinated sales at over 200 Hartford stores, including Brown Thomson’s, Sage Allen, Steiger’s, Wise-Smith, and G. Fox, will draw thousands downtown. “The free bus ride³ program is not a ‘gimmick.’ It is being promoted to stress the need for the public to use buses and not clog downtown arteries and parking areas.” Thirty buses³ have been added for the occasion. “The promotion³ is not a reimbursement program wherein bus riders have to purchase goods to get their fare back. Shoppers will just step aboard a bus without paying any fare within the first fare limit and The Connecticut Co. will bill the retail board.”

For those who are reading this before coffee, I will come right out and say April Fools!

But this all happened, just not in 2023.

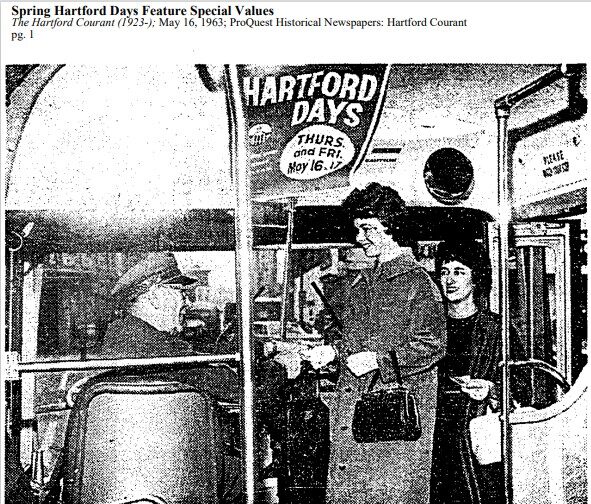

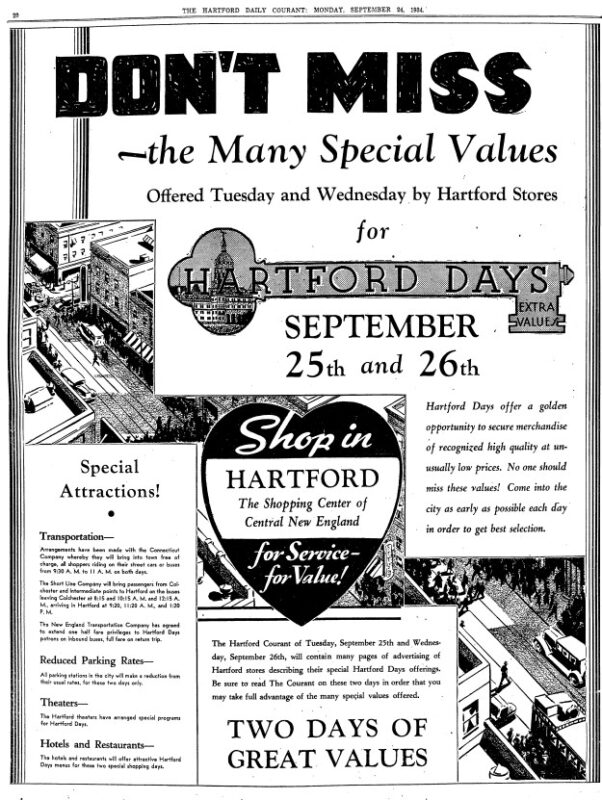

Hartford Days — which went by several other names, including Million Dollar Hartford Days, Spring Hartford Days, and Downtown Hartford Days — were as described, from (as far as I can tell) September 1934 to May 1978, with a few periods of several years where this event was on hiatus. For most of its span, free inbound rides were available during a 9:30-11:30 or 9:30-10:30 AM window, for those in what we would now call the “local service zone.” Those who would rely on an Express bus had a fare discount. At least once, in 1963, the free fare was extended to buses running in early evening hours as well.

Every year, there was a large spread in the Courant highlighting this event, as well as the free transportation service. The buses were, by their reports, full. Give people free transportation and we will use it.

Well, what happened?

There were no full page spreads explaining the tumbleweeds, and there is rarely one cause for anything. So, pick a reason. There were the racial tensions in the late 60s and early 70s that linger today. The Vietnam War was at its peak. People gave up silly pursuits like spending their days and money on obtaining stuff. April Fools on that last one! More accurate, people were opting out of using walkable urban centers because driving to suburban strip malls was more aligned with their lifestyle. It did not help that Westfarms opened in the 1970s and several downtown merchants opened up shop in that, giving people less reason to make a trip to downtown Hartford.

But, wanting to get people to use the bus became increasingly important, not simply as a way to make driving and parking less irritating during special sale events. After rapidly degrading the environment over the previous several decades, people were waking up to the losses.

There was a 121 day bus strike in the early 1970s and ridership did not immediately rebound. A few weeks after it ended, ridership was reportedly only at 67% of its pre-strike levels. The Greater Hartford Chamber of Commerce, at the urging of the governor, scrambled to put together a plan to get people back on buses. They lobbied major employers to reduce employees’ bus fares much as they were already subsidizing employee parking. They tried pushing for a return of free bus rides for shoppers, for at least a month of Thursdays and Saturdays. They remarked that G. Fox was already providing free bus passes for their patrons. The plan also included marketing.

By then, economic disinvestment in cities and estrangement from our environment was in full effect. The event that had included hundreds of businesses now had fewer than fifty participating. To make it worse, Connecticut Department of Transportation got involved, and thus, a wildly convoluted system was born. From 1974-1977, instead of giving shoppers a hassle-free and fare-free transportation experience, they got something complicated and gimmicky. It was gamified. Strings were attached. Passengers would board and pay their fare. The driver would give them a “ticket with four stubs.” After the person made a minimum purchase of $5 at a participating retailer, they were handed a quarter. At most they could earn two quarters back from the same merchant. While this ultimately amounted in reimbursement for their round trip, plus an additional bus pass — except they were given money, not a ticket — you have to ask why so many hoops were required. If someone needs an advanced degree to understand a scheme, it’s flawed.

During that time, there were no breathless fluff pieces about how packed the buses were, and we can guess why. For what appears to be the final Hartford Days in 1978, there was no mention at all of sweet transportation deals. Instead, it was the Chamber of Commerce begging major employers to give workers an extended lunch break so they could shop. SNET, with its offices in the West Service Road boonies at the time, provided shuttle service downtown for its own staff. So that was that.

But Hartford Days were not the only time Connecticut’s buses have been free. In March 1975, The Bushnell began a bus ticket refund program and funded a free shuttle that would connect patrons from several downtown parking lots to the performing space. In late 1979, bus rides were free for about one month in a section of Windsor that had been ravaged by a tornado.

Then, there were a series of free trials when new bus routes opened. We saw this not so long ago when rides were free for the first week of CTfastrak‘s operation. When New London got bus service in 1980, their three buses were free for three days. The CT DOT commissioner in 1980 — coming on 43 years ago — said that “with 97 percent of commuters driving their cars to work ‘we are dependent on gasoline to the degree that we face rising prices and shortages in the future unless we turn to buses and trains.'” We are now in the future and not nearly enough people have turned to buses and trains. Three years later, there was free Saturday bus service on a new route between Clinton and Old Saybrook for a two and a half month trial period. The towns of Clinton and Westbrook picked up the tab; Old Saybrook apparently did not.

In 1990, perhaps because someone was sentimental for the convoluted bus reimbursement scheme of Hartford Days’ final years, people were able to try the bus from Simsbury to Hartford not by simply boarding, but after exchanging coupons for bus tokens that had been mailed to their homes or found in locations around town. Despite this silly extra step, people showed up at 6 AM to give it a whirl. At other times there were free shuttle buses in Norwalk; free bus rides for one month between Hartford and Middletown, and then Middletown to New London.

Not long after the first Earth Day, getting people out of their cars and onto public transportation — for more than just a shopping trip or to meet a new bus route — became a topic that would not go away, in part because the answers are right in front of us, but the political will has been lacking. Make no mistake, this is not an April Fool’s joke. This is an indictment of multiple generations.

At the Greater Hartford Council on Economic Education Conference in 1971, the concept of permanent fare-free buses was floated out and a major backer of this was the Amalgamated Transit Union in New Haven. You read that right. The bus union supported fare-free public transit in 1971.

In 1975, a petroleum company — Arco — solicited ideas for conserving energy, and the Hartford Courant published several of what people submitted; the paper encouraged readers to send their ideas to DOT headquarters. One concept given considerable space was that of “a free, efficient, and convenient nationwide public transportation system [that] would represent a vast improvement in the quality of life for every citizen — surely at less cost than that of maintaining present institutions with their implications for depletion of resources, destruction of the environment, urban congestion, sacrifice of life, and isolation of not just the young, the elderly, and the poor, but in fact most of us from the society of which we are a part.” While the Courant did not outright endorse this idea, the seeds had obviously been planted because by 1979, the paper ran an editorial in response to the bus companies’ desire to increase fares: “Buses have a higher fuel efficiency per passenger than automobile and they help reduce air pollution. Cities, trucking companies, and automobile commuters benefit from the highway traffic reduction that results from bus service. Because of such benefits, fares are kept lower in some states than in Connecticut. In a few cities, some transit rides are free.”

Attempting to raise fares when service was trash — my paraphrase of what was in the Courant editorial — did not go unanswered. In February 1980, Hartford’s Corp. Counsel — Alexander Goldfarb, who has a pocket park named after him at the corner of Broadview Terrace and Grafton Street — announced that the City of Hartford would file a lawsuit to block fare increases. It took a year, but the state Supreme Court said, you know what, that 40% fare increase’s procedure was absolutely illegal. Before that ruling was in, Connecticut Transit had been ordered to issue passengers receipts so that they could get refunded if CTtransit lost the lawsuit. Imagine if our local governments today had the courage to do more than simply shrug.

If you have been to Mansfield in the last few years, you may have found yourself a bit disoriented by all the new development, but also waiting for a bus at the Nash-Zimmer Transportation Center. Dennison Nash was another person with actual guts. Back in 1993, when you could still find the Sugar Shack at Storrs, Eastern Connecticut Transit Alliance pitched the idea of fare-free bus service between Storrs and Willimantic. At the time, UConn was substantially less built-up, and one cannot live on Sugar Shack alone. Alliance member Dennison Nash said that “the whole aim is to get the cars off the road” to improve air quality, and as for funding, he thought that the university should foot the bill.

Over the next few weeks, the funding source evolved so that UConn would pay half the fee, and then the towns of Mansfield and Windham would equally pay the other half. There was some negotiation involved, but Nash pushed for a fare-free run for one year, saying that then they could think about what adjustments to service should be made. Six months later, the free trial period began. The outcome, if you have been paying attention this whole time, was predictable: when a bus goes somewhere useful and it is free, people will ride the hell out of it. The Windham Region Transit District surveyed 221 riders in April about the free rides that began the previous November, and what they learned was that 30% of those surveyed had not been on a WRTD bus before the free trial. Ridership on this route increased 31% in the first seven months of the experiment, which was a 51% increase over where it had been when Nash began asking for Connecticut residents to go wild and try something different.

Even the Courant seemed sold: “The experiment of offering some people [UConn community along with Mansfield residents] no-fare bus rides between Willimantic and Storrs appears to have attracted new riders and removed cars from the busy highways.”

The last story I’ll leave you with is one that shows another time that buses, sort of, were free. In November 1920, jitney drivers protested how Hartford’s City Council restricted where they could run. These smaller buses — probably smaller than some of the eyerollingly ginormous SUVS on the roads now — were not allowed on the same roads as the streetcars. Drivers fought this by offering free rides — loophole — on these routes while handing out flyers to passengers “with a view to protecting the trolley lines in their excessive charge of 10 cents for fare and in the face of a protest by their own members for inadequate service, even at the increased fare, by the Connecticut Company.”

In short, they wanted the capitalist dream. For the next several years, the jitney drivers bickered with the Connecticut Company until finally something was worked out so that there were coordinated fares and transfers between trolleys and buses. And long story short, the Connecticut Company became absorbed into what is now CTtransit.

What have we learned here today?

1. Anyone who says something can’t be done needs to spend a few quiet evenings alone with a pile of old newspaper articles that say otherwise

2. Fare-free bus service is not a new idea, not even in Connecticut

3. If you want tiny parks and bus stations named after you, then do something to earn it. Inaction ain’t it.

4. When a bus goes somewhere useful and it is free, people will ride

¹ Hartford Courant, July 1952

² Hartford Courant, July 1959

³ Hartford Courant, February 1958

Hartford Days Are Here Again!

Downtown merchants, restaurants, and theaters will be offering discounts as part of this year’s Million Dollar Hartford Days. Besides the most exclusive bargains, early bird shoppers will be treated to door-to-door free bus service.

“Buses were full Tuesday¹ with early birds taking advantage of the merchants’ offer.” Through the Chamber of Commerce, retailers are paying the bus company to make transportation convenient for shoppers during Hartford Days. “Some buses arriving at the downtown starting lane² during the mid-morning were filled to standing-room only.”

The coordinated sales at over 200 Hartford stores, including Brown Thomson’s, Sage Allen, Steiger’s, Wise-Smith, and G. Fox, will draw thousands downtown. “The free bus ride³ program is not a ‘gimmick.’ It is being promoted to stress the need for the public to use buses and not clog downtown arteries and parking areas.” Thirty buses³ have been added for the occasion. “The promotion³ is not a reimbursement program wherein bus riders have to purchase goods to get their fare back. Shoppers will just step aboard a bus without paying any fare within the first fare limit and The Connecticut Co. will bill the retail board.”

For those who are reading this before coffee, I will come right out and say April Fools!

But this all happened, just not in 2023.

Hartford Days — which went by several other names, including Million Dollar Hartford Days, Spring Hartford Days, and Downtown Hartford Days — were as described, from (as far as I can tell) September 1934 to May 1978, with a few periods of several years where this event was on hiatus. For most of its span, free inbound rides were available during a 9:30-11:30 or 9:30-10:30 AM window, for those in what we would now call the “local service zone.” Those who would rely on an Express bus had a fare discount. At least once, in 1963, the free fare was extended to buses running in early evening hours as well.

Every year, there was a large spread in the Courant highlighting this event, as well as the free transportation service. The buses were, by their reports, full. Give people free transportation and we will use it.

Well, what happened?

There were no full page spreads explaining the tumbleweeds, and there is rarely one cause for anything. So, pick a reason. There were the racial tensions in the late 60s and early 70s that linger today. The Vietnam War was at its peak. People gave up silly pursuits like spending their days and money on obtaining stuff. April Fools on that last one! More accurate, people were opting out of using walkable urban centers because driving to suburban strip malls was more aligned with their lifestyle. It did not help that Westfarms opened in the 1970s and several downtown merchants opened up shop in that, giving people less reason to make a trip to downtown Hartford.

But, wanting to get people to use the bus became increasingly important, not simply as a way to make driving and parking less irritating during special sale events. After rapidly degrading the environment over the previous several decades, people were waking up to the losses.

There was a 121 day bus strike in the early 1970s and ridership did not immediately rebound. A few weeks after it ended, ridership was reportedly only at 67% of its pre-strike levels. The Greater Hartford Chamber of Commerce, at the urging of the governor, scrambled to put together a plan to get people back on buses. They lobbied major employers to reduce employees’ bus fares much as they were already subsidizing employee parking. They tried pushing for a return of free bus rides for shoppers, for at least a month of Thursdays and Saturdays. They remarked that G. Fox was already providing free bus passes for their patrons. The plan also included marketing.

By then, economic disinvestment in cities and estrangement from our environment was in full effect. The event that had included hundreds of businesses now had fewer than fifty participating. To make it worse, Connecticut Department of Transportation got involved, and thus, a wildly convoluted system was born. From 1974-1977, instead of giving shoppers a hassle-free and fare-free transportation experience, they got something complicated and gimmicky. It was gamified. Strings were attached. Passengers would board and pay their fare. The driver would give them a “ticket with four stubs.” After the person made a minimum purchase of $5 at a participating retailer, they were handed a quarter. At most they could earn two quarters back from the same merchant. While this ultimately amounted in reimbursement for their round trip, plus an additional bus pass — except they were given money, not a ticket — you have to ask why so many hoops were required. If someone needs an advanced degree to understand a scheme, it’s flawed.

During that time, there were no breathless fluff pieces about how packed the buses were, and we can guess why. For what appears to be the final Hartford Days in 1978, there was no mention at all of sweet transportation deals. Instead, it was the Chamber of Commerce begging major employers to give workers an extended lunch break so they could shop. SNET, with its offices in the West Service Road boonies at the time, provided shuttle service downtown for its own staff. So that was that.

But Hartford Days were not the only time Connecticut’s buses have been free. In March 1975, The Bushnell began a bus ticket refund program and funded a free shuttle that would connect patrons from several downtown parking lots to the performing space. In late 1979, bus rides were free for about one month in a section of Windsor that had been ravaged by a tornado.

Then, there were a series of free trials when new bus routes opened. We saw this not so long ago when rides were free for the first week of CTfastrak‘s operation. When New London got bus service in 1980, their three buses were free for three days. The CT DOT commissioner in 1980 — coming on 43 years ago — said that “with 97 percent of commuters driving their cars to work ‘we are dependent on gasoline to the degree that we face rising prices and shortages in the future unless we turn to buses and trains.'” We are now in the future and not nearly enough people have turned to buses and trains. Three years later, there was free Saturday bus service on a new route between Clinton and Old Saybrook for a two and a half month trial period. The towns of Clinton and Westbrook picked up the tab; Old Saybrook apparently did not.

In 1990, perhaps because someone was sentimental for the convoluted bus reimbursement scheme of Hartford Days’ final years, people were able to try the bus from Simsbury to Hartford not by simply boarding, but after exchanging coupons for bus tokens that had been mailed to their homes or found in locations around town. Despite this silly extra step, people showed up at 6 AM to give it a whirl. At other times there were free shuttle buses in Norwalk; free bus rides for one month between Hartford and Middletown, and then Middletown to New London.

Not long after the first Earth Day, getting people out of their cars and onto public transportation — for more than just a shopping trip or to meet a new bus route — became a topic that would not go away, in part because the answers are right in front of us, but the political will has been lacking. Make no mistake, this is not an April Fool’s joke. This is an indictment of multiple generations.

At the Greater Hartford Council on Economic Education Conference in 1971, the concept of permanent fare-free buses was floated out and a major backer of this was the Amalgamated Transit Union in New Haven. You read that right. The bus union supported fare-free public transit in 1971.

In 1975, a petroleum company — Arco — solicited ideas for conserving energy, and the Hartford Courant published several of what people submitted; the paper encouraged readers to send their ideas to DOT headquarters. One concept given considerable space was that of “a free, efficient, and convenient nationwide public transportation system [that] would represent a vast improvement in the quality of life for every citizen — surely at less cost than that of maintaining present institutions with their implications for depletion of resources, destruction of the environment, urban congestion, sacrifice of life, and isolation of not just the young, the elderly, and the poor, but in fact most of us from the society of which we are a part.” While the Courant did not outright endorse this idea, the seeds had obviously been planted because by 1979, the paper ran an editorial in response to the bus companies’ desire to increase fares: “Buses have a higher fuel efficiency per passenger than automobile and they help reduce air pollution. Cities, trucking companies, and automobile commuters benefit from the highway traffic reduction that results from bus service. Because of such benefits, fares are kept lower in some states than in Connecticut. In a few cities, some transit rides are free.”

Attempting to raise fares when service was trash — my paraphrase of what was in the Courant editorial — did not go unanswered. In February 1980, Hartford’s Corp. Counsel — Alexander Goldfarb, who has a pocket park named after him at the corner of Broadview Terrace and Grafton Street — announced that the City of Hartford would file a lawsuit to block fare increases. It took a year, but the state Supreme Court said, you know what, that 40% fare increase’s procedure was absolutely illegal. Before that ruling was in, Connecticut Transit had been ordered to issue passengers receipts so that they could get refunded if CTtransit lost the lawsuit. Imagine if our local governments today had the courage to do more than simply shrug.

If you have been to Mansfield in the last few years, you may have found yourself a bit disoriented by all the new development, but also waiting for a bus at the Nash-Zimmer Transportation Center. Dennison Nash was another person with actual guts. Back in 1993, when you could still find the Sugar Shack at Storrs, Eastern Connecticut Transit Alliance pitched the idea of fare-free bus service between Storrs and Willimantic. At the time, UConn was substantially less built-up, and one cannot live on Sugar Shack alone. Alliance member Dennison Nash said that “the whole aim is to get the cars off the road” to improve air quality, and as for funding, he thought that the university should foot the bill.

Over the next few weeks, the funding source evolved so that UConn would pay half the fee, and then the towns of Mansfield and Windham would equally pay the other half. There was some negotiation involved, but Nash pushed for a fare-free run for one year, saying that then they could think about what adjustments to service should be made. Six months later, the free trial period began. The outcome, if you have been paying attention this whole time, was predictable: when a bus goes somewhere useful and it is free, people will ride the hell out of it. The Windham Region Transit District surveyed 221 riders in April about the free rides that began the previous November, and what they learned was that 30% of those surveyed had not been on a WRTD bus before the free trial. Ridership on this route increased 31% in the first seven months of the experiment, which was a 51% increase over where it had been when Nash began asking for Connecticut residents to go wild and try something different.

Even the Courant seemed sold: “The experiment of offering some people [UConn community along with Mansfield residents] no-fare bus rides between Willimantic and Storrs appears to have attracted new riders and removed cars from the busy highways.”

The last story I’ll leave you with is one that shows another time that buses, sort of, were free. In November 1920, jitney drivers protested how Hartford’s City Council restricted where they could run. These smaller buses — probably smaller than some of the eyerollingly ginormous SUVS on the roads now — were not allowed on the same roads as the streetcars. Drivers fought this by offering free rides — loophole — on these routes while handing out flyers to passengers “with a view to protecting the trolley lines in their excessive charge of 10 cents for fare and in the face of a protest by their own members for inadequate service, even at the increased fare, by the Connecticut Company.”

In short, they wanted the capitalist dream. For the next several years, the jitney drivers bickered with the Connecticut Company until finally something was worked out so that there were coordinated fares and transfers between trolleys and buses. And long story short, the Connecticut Company became absorbed into what is now CTtransit.

What have we learned here today?

1. Anyone who says something can’t be done needs to spend a few quiet evenings alone with a pile of old newspaper articles that say otherwise

2. Fare-free bus service is not a new idea, not even in Connecticut

3. If you want tiny parks and bus stations named after you, then do something to earn it. Inaction ain’t it.

4. When a bus goes somewhere useful and it is free, people will ride

¹ Hartford Courant, July 1952

² Hartford Courant, July 1959

³ Hartford Courant, February 1958

Related Posts

Dandelion Season?

Place This Place

Scarborough Family Fires Back