Three pedestrians and two cyclists were killed during May 2020, at a time when Lamont’s lockdown order was entirely in effect until May 20th. All but one of those fatal injuries were incurred before the first phase of re-opening.

The first day of the month was when two pedestrians and one cyclist were fatally injured in three separate incidents. Raymond Colangelo, 54 of Hartford, was hit at 4:20 in the morning while crossing the street near Goodwin Park’s Maple Avenue entrance, just around the corner from his home. The driver remained on scene, but there was no report of any charges filed; the vulnerable user law was apparently not applied.

Later that morning in Middletown, Louis Petruzzello, 64, reportedly rode his bicycle into the back of a dump truck that was stopped in the road — which admittedly sounds puzzling considering how athletic Petruzzello had been. He leaves a wife and son to mourn him.

At 8:45 that evening, Shaneice Copeland, 31, was struck by a BMW X3 while she attempted to cross the road. This happened about one block away from the hospital to which she was taken, and in which she died about two hours later. Ms. Copeland loved music and dance. The manager of Taco Bell leaves behind the family she loved, including her son and daughter who are now motherless.

The driver, Christopher Bolden, drove off like a coward. He was later arrested and charged with evading responsibility; there has been no mention of applying the vulnerable user law.

Two days later, Connecticut lost another person: an unnamed toddler in Willington.

Just after 5 PM on a sunny day, a three-year old boy was struck in the 400 block of Tolland Turnpike. This child died later in the evening from his injuries.

There has been no followup from the local media and no identification of the driver, even though nothing indicated that this was a hit-and-evade responsibility situation.

Again, no mention of the vulnerable user law. Is there anyone more vulnerable than a toddler?

On the second day of Connecticut’s partial re-opening, 79-year old Julio Ruiz was riding his bicycle in New Haven when he was struck by a motorcycle. Its cowardly operator took off. Ruiz later died from his injuries.

Could you imagine being told that a friend lost her father from COVID-19, and before an expression of sincere sympathy, before giving solace to the bereaved, you instead asked if her father had stayed home, worn a mask, maintained physical distance, washed his hands with soap and water, and refrained from touching his face? What sort of careless thing did he do to expose himself?

Of course not.

There is a line between asking how something could have happened, and asking how the victim could have allowed it to happen to them.

Yet, when we talk about pedestrian fatalities, there are many who do not refrain from callous and misguided speech.

Read the non-curated comments on any article reporting pedestrian deaths. Even if the facts are in the aforementioned article, there will be at least one person — usually more — doing a “what about those jaywalkers who dart out in front of me.” Besides continued, pervasive use of the word “accident,” is there any evidence more overt that as a society we refuse to accept responsibility for protecting the safety and lives of others?

Let’s talk about the jaywalker.

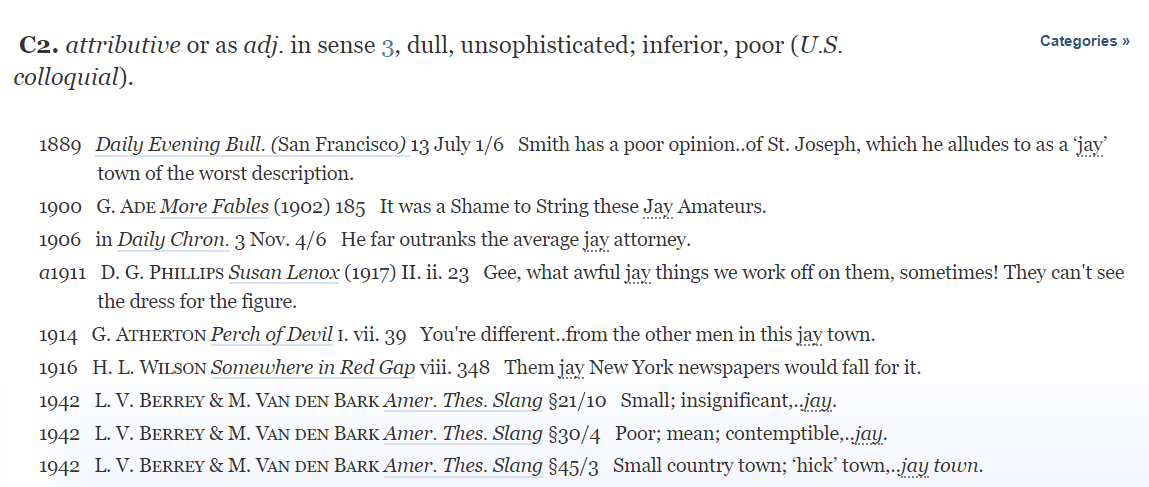

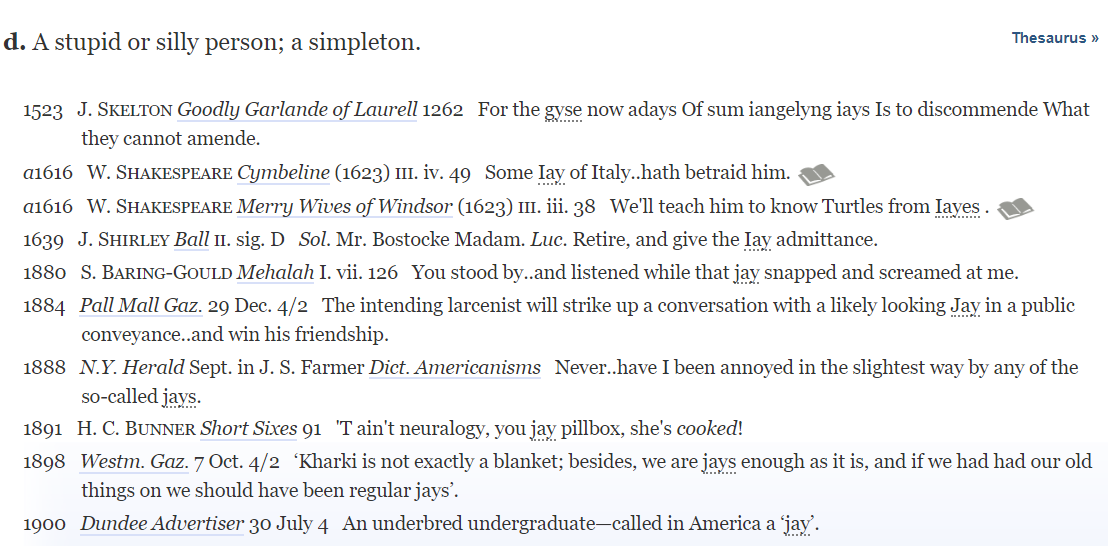

The Oxford English Dictionary (see images above) notes that a “jay” is a stupid or silly person, a simpleton. In the United States, the word was used to describe someone who was poor, considered unsophisticated or inferior. Basically, a hick.

Can you imagine any other context in which it is acceptable for a victim to be called a slur? To say what amounts to “Jane Smith done got herself killed because she’s a hick”?

How did we come to embrace this slur to describe people walking in places deemed inconvenient to drivers?

Before we talk about that, we need to look at a (possibly temporary, possibly not) shift happening at the moment, right here.

For reasons related to the COVID-19 lockdown, the City of Hartford recently closed nearly every park road to motor vehicle traffic. The only segments that have been left open are to allow drivers access to parking lots adjacent to the golf courses in Keney and Goodwin Parks. There are no gatekeepers and nothing to prevent those needing access from using those lots.

These closures are openings.

They have opened good, paved roads up for people-centered use, from those learning to ride their bicycles to people strolling for much-needed exercise. Instead of being shunted down narrow paths, like those in Elizabeth Park, visitors can now enjoy the freedom to move without being in a state of constant alert for cars. Because the paths in certain parks were challenging for those with mobility devices, this change has actually improved accessibility.

Imagine this being more or less the norm, until one day a well-funded industry decides to strong arm everyone into giving up this glorious freedom. What if through a combination of street design and ad campaigns, they found a way to reverse our ability to walk and roll in these parks, making it so you could only drive through them?

What if? That’s basically how most of our world has operated in recent memory. During the pandemic, a friend stopped by a chain drugstore in Greater Hartford to pick up her prescription. She forgot her mask, so the option was to either use the drive-thru or go home, get her mask, and return. A store employee chastised her for riding her bicycle through the drive-thru, claiming it was too dangerous because of all the cars. This is a store that chose to do a major renovation of the building and lot several years ago. Any danger present was one that they themselves created by not thinking of how to design for the safety of all customers.

These scenarios exist at once: parks and some streets devoted for people-first use and other places that prioritize the automobile and those within it over all else.

We have the opportunity to choose which reality we want to be dominant from here on out, regardless of what tricks our memories play on us. Here’s the thing about recent memory: it does not stretch to include all of history or what norms prevailed at other times.

There was a time when the public would be outraged whenever a pedestrian was killed, and it did not matter if that person was in a crosswalk or not. There had been a time before crosswalks. The assumption had been that people had the right to walk wherever they saw fit. For the most part, they had no reason to question that assumption when sharing space with horses, trolleys, and bicycles. That’s not to say that there were never collisions or other incidents, but that the widespread understanding was that the space was for all users; it was not the domain of any one group, with crumbs tossed to the users determined to be lesser than.

There was fury and resentment over the car encroaching on public space. This created a public relations nightmare for the automotive industry, and they opted to retaliate. Peter Norton has written extensively about this in his book Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City.

Norton explains that there was not an immediate surrender of the street by those using it sans automobile. Much of the early twentieth century was spent grappling with the question of what and who is the street for. Norton writes: “In 1910, the answers would have varied with the affected social group, including parents, pedestrians, streetcar riders, and motorists. But most — including many motorists — would have agreed that streets were not for fast driving, and that motorists who drove faster than pre-automotive vehicles were alone responsible for any harmful consequences.” But to “secure an urban future for the car, [motoring advocates] would have to win a legitimate place for it in the street and cast doubt on the legitimacy of those who stood in the way.”

Their campaign was effective. Not immediately, but if you look at the attitude now when a pedestrian dies, you see the series of questions: Were they in the crosswalk? Did they have the walk signal? Were they wearing hi-vis? Did they carry a surrender flag? Did they look both ways? Were they under the influence of anything? Did they look both ways twice? Did they have absolutely perfect conditions before proceeding, or did they behave suicidally (as motordom often put it) by not waiting for such unicorn conditions to reveal themselves?

Car manufacturers and car clubs, referred to as ‘motordom’ by themselves and the papers of the time, began running content passed off as news. The sometimes daily reports started playful, selling readers on the joy of pleasure driving and sharing tips for how to maintain the vehicle; we may forget today that early automobiles required more know how from the operator than the ones of today, and even running headlamps was more complicated then.

An occasional political piece would appear. A New York Times headline from 1913 reads: “Fight Urged on Auto Speed Traps: Resistance to Fine Payment Advocated by NY State Automobile Association.” They returned to business as usual until 1917 when the NY State Automobile Association pushed to abolish toll bridges, which they dubbed ‘antiquated.’

What sustained motordom’s attention, however, was the pedestrian — viewed alternately as an obstacle to vehicles, physically, and as an obstacle to turning every American into a car owner.

In 1913 Connecticut’s own newspaper, the Hartford Courant, ran a piece that only quoted the president of Detroit’s Maxwell Motor Company, who claimed that problems on the roadways are mostly the fault of pedestrians, and that the “remedy is in proper traffic regulations for pedestrians — rigidly enforced.”

This was not the Courant‘s only flirtation with publishing poorly sourced items. “The Sunday Motorist,” edited by William Ullman, printed in 1924 was on the topic of motorists when they are pedestrians: “When you walk try to think of yourself as a driver of a car that is nearest you. Recall the things you thought of when the last pedestrian suddenly stepped into your way. . . . By all rules of logic the good driver ought to be a good walker in traffic for he alone knows the great disadvantage to which the driver is so frequently put when he is endeavoring to compensate for the carelessness of pedestrians.”

That reveals a shift on ideas about how roadways should be used and to whom blame is freshly being assigned for when chaos ensues.

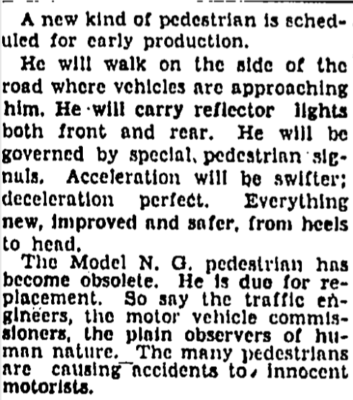

By 1932 the Hartford Courant was running unattributed pieces, such as this:

Such agenda-laden pieces continued in the papers, with motordom publishing blanket statements left unchecked by the media nationwide.

One of these was published by the New York Times in 1938: “Car owners and operators are becoming better drivers, but men and women who cross the streets or walk the country roads are becoming more careless.” That statement, issued by the president of the Automobile Club of New York, was in a short piece that contained quotes from nobody else except him. No medical professionals were consulted. It was printed as if every word he said was the truth.

The victim blaming was not always so blatant or one-sided. The National Safety Council found an audience for its message through the Courant in 1923. In this piece, they acknowledged four important things: it takes at least two for there to be a pedestrian-motorist collision, bad drivers exist, insufficient infrastructure motivates people to step into the street, and “jaywalking” is deadly for pedestrians but is a mere inconvenience for drivers: “[The pedestrian] keeps the motorist in constant suspense and causes the hair of motorman to turn gray before its time. . . . Sometimes the sidewalk isn’t wide enough for him and he walks in the streets. . . . The jay walker may seem to bear a charmed life but some day he is sure to meet a jay driver.”

Even in 1950, there was a degree of controversy. The New York Times responded to pressure from the Broadway Association to crackdown on jaywalking, admitting that freewalking can cause problems, but that there is “the need for more effective regulation of manners of motorists in order to eliminate the bulk of our traffic hazards” as “many motorists are prone to believe the streets are their exclusive property and in their vying for the right of clear passage with other motorists often neglect the rules designed to afford safe passage to both pedestrians and drivers.”

By 1958, though, New York was instituting what were called both “anti-jaywalk rules” and “pedestrian protection rules,” though both referred to the same thing: fining pedestrians for not obeying lights.

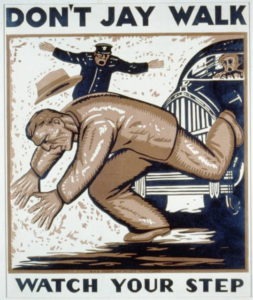

Between the industry opinion pieces passed off as valid news in the papers, indoctrination of children through poster contests, and other such efforts, motoring advocates won the battle of “whose streets?” — at least until recently.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which has exposed many pre-existing injustices, has especially shone a light on how our streets have not been serving people. There have been efforts to change this for the time being, and hopefully, for good. That is what we need to decide going forward: are we going to be the kind of people who pathologize natural movement and make access to food, medical treatment, and masks dependent on one’s ownership of a car, or will we choose to put people first?

Meanwhile, Connecticut has lost 24 pedestrians this year, seven of which obtained their fatal injuries during the full lockdown period.