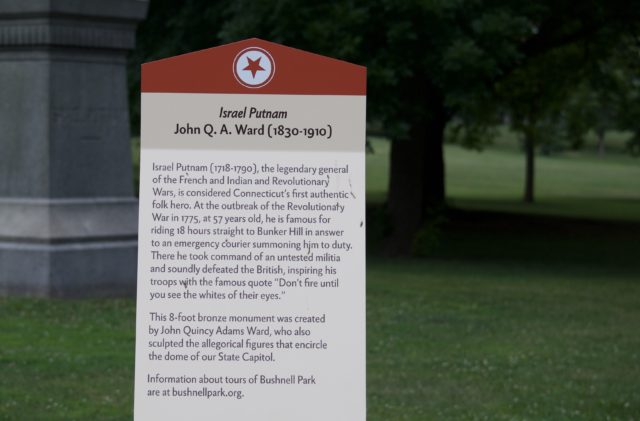

New signs have been installed near monuments in Bushnell Park, giving some information about the statues’ creators along with the person depicted on the pedestal.

What this particular plaque neglects to mention is that Israel Putnam is regarded as being responsible for killing the last timber wolf in Connecticut.

A large number of livestock were apparently taken down by a wolf in Brooklyn, where Putnam lived. The number that gets mentioned most often is 70, but more likely it was a fraction of that. Local farmers killed her pups over several seasons, but could not catch her. No explanation was provided as to how she continued to give birth while being the last mature wolf around. Other tellings say this was the last “she-wolf” in the state.

In 1899, a gray wolf reportedly treed two men on Cedar Mountain (Hartford/Newington/Wethersfield), though there was speculation that the scared young sirs who escaped harm had really only been chased by a small dog. A man traveling through Sharon reported seeing one in 1905, which was suspected of having escaped captivity. These sporadic sightings may seem far-fetched, but remember that the bobcat, once nearly extinct, is seeing its population grow once again.

A tale from London described Putnam as not killing a wolf, but a bear and several of her cubs. You can see how rumors get started.

Anyway.

Angry over the livestock massacre, Putnam and others began tracking the wolf, a feat that became easier after she lost part of her paw in a trap. With help from bloodhounds, they tracked her three miles from Putnam’s home to a cave in what is now Mashamoquet Brook State Park. As one legend has it, he tied a rope around his legs so that his neighbors could pull him out. After spying the wolf, his hunting companions yanked him out of harm’s way — reportedly causing him to lose his clothing in the process. One story only names his shirt as being lost in the commotion. Once out, he grabbed and loaded his gun, went back in, and shot the wolf. He had his companions pull him once more from the smoky den. He entered a third time to confirm his kill and drag the wolf out. It would be put on public display after.

What is buried in that legend, which some believe exemplifies courage, is that while on this excursion, Putnam did not take the initiative to climb inside the cave and murder the animal that was simply doing what it was designed to do. He had asked someone else to do his dirty work first: a Black man whom Putnam enslaved. It is not known what, if any, consequences there were for declining what may have been a request, or may have been an order. He also tried to convince his dog and the farmers to go inside — they all told him a Winter 1742-1743 version of “Hell no!”

In most tellings of this tale, it’s only noted that others in the hunting party did not want to go in the cave, and there is no mention of the role others played in the event. Accounts published during the patriotic fervor in 1976, for instance, completely removed pieces of this story. Here’s one version:

Here’s another version from the same year:

Can we get more American than to erase the role others have played in our success stories? Without help from his neighbors, Putnam would’ve been staring down a cornered wolf without his gun, and that would’ve been that.

There are those who would say that Putnam was behaving as a man of his time, and that we should not hold those from the past up to our standards. They say we should judge only by the values of the time.

Whose values?

Those of his neighbors, who seemed to have the sense not to crawl inside a wolf’s den?

Those of the colonists who radically modified and subjugated the land for agriculture, and who had not built fences adequate for keeping out predators?

Those of the Mohegan and Nipmuck, who lived in this area for years, unbothered by wolves doing wolf things? Who had a complex relationship with the animal, viewing it as more than just a predator?

By now we should know that there is never one singular narrative.

Richard Nelson

First let me say I love your work and I check out Real Hartford everyday. Now a thought on this article.

Holding people of the past to our standards has always given me a tickle. Recently in an essay that I did for furbirdsqueerly I tried to put that notion to rest by simply stating, I reject that with the names of those in that time who knew better and who spoke out.

I am concerned with both versions of this story. How to make a fool into a glorious hero. But of course, how can I not love the first where even “brimstone could not dislodge her.” In one night 70 sheep and goats were lost? The wolf must have been one hungry wolf or one pissed off wolf. This type of history happens all the time with many versions of white amerikkkan history. Let us hope that we can get rid of the flowery, the rose spectacles, the sanitized and the distorted history of empire and do it soon. While we are at it, I wonder about those who denounce the 1 % of today and have to ask is there any room to denounce the 1% of yesterday? Will the voices who denounce the 1% of today be lost to history and folks in the future will say, “oh that is just the way it was back then?

Let’s not forget that this man, Israel Putnam was a slave owner and first was willing to sacrifice this enslaved man to get the wolf. Maybe we should re-think the story of Putnam and his right to be up on a pedestal.