It will soon cost motorists more to rent car storage on certain downtown streets in Hartford. As of Monday, August 5, 2019, if you want to store your car on the street in the core of downtown, it will cost $2 per hour. The $1 per hour rate remains in place for streets outside this zone.

There are ways to get around paying more, but first, let’s step back about a century.

As the private automobile increased in popularity, people needed to figure a few things out, one of which was parking. Without protocols in place, people would leave their cars wherever, however, for however long they wanted. Who and what roads were for was still being determined. Trolleys, along with horse-drawn carriages, bicycles, people, and push carts were all sharing the streets when the horseless carriage came onto the scene. There was a lot going on. Congestion was determined to be a widespread problem, though some at the time felt this was overstated as an excuse used by those profiting from construction projects.

In the summer of 1922, Hartford formed a committee to look into machines that would allow motorists to rent storage space on the street for their vehicles. This went exactly nowhere.

In 1930, the “parking problem,” as so many called it, was raised again. This time, proponents were looking to do some slum clearance, with numerous letters to the editor that year calling for what they called socialism. One of these letters said: “Many European cities, however, do not hesitate to appropriate large sums of money for the abolition of slums in the belief that the expenditure yields a larger return in all those things that make for human values.” Hold on, y’all. Wait for it. The letter writer explains these values: “We have presented the suggestion that Hartford might make an important contribution to slum elimination by condemning some of the property on which tenement shacks stand and converting it into parking plazas for automobiles.” Not one of these anonymous letters advocated for rebuilding healthier housing on the former tenement sites. (Spoiler alert: Check out all the surface parking on Sheldon Street.)

It took until 1936 for parking meters to be considered once again. Fourteen years. If you think that’s the end of the story, you must not have lived in Connecticut long. Questions of legality are raised. There are letters to the editors of local newspapers. One published in the Hartford Courant in 1936 reads: “It is the duty of growing communities like Hartford to consider provision for free adqeuate parking space as part of its highway system.” Say what? That same letter put forth the same worries that we hear today: if people have to pay to park, they won’t come to Hartford anymore.

(Spoiler alert #2: Free parking in the suburbs is not what caused mass urban depopulation.)

By 1937, most anything that could be considered a small city, or larger, was toying with the prospect of parking meters.

Hartford might be the Irony Capital of the World. People were annoyed, feeling like their rights were about to be trampled upon. Others called it a racket, despite it being said from the very beginning that the aim of metered parking was not to generate revenue for the City of Hartford. Despite this outrage, paying for parking should actually be a very Hartford thing, and here’s why: Hartford was home to not one, but two, companies that manufactured parking meters.

M.H. Rhodes on Bartholomew Avenue, creator of electrical switches, got into the meter game, naturally. They had contracts in Boston, Seattle, and Cleveland, among other places, and had been regarded as one of the largest manufacturers of parking meters in the world, at least in 1958. The Veeder-Root company on Sargeant Street was producing for Standard Meter Corp. Both were profiting off other cities’ streets by 1937.

That year, Providence installed meters on a trial basis. Hartford initially said it would look to see how this neighboring state’s capital managed, but in 1938 determined it was impossible to study because the trial meters were installed areas that all happened to be impacted by flood waters.

In 1939, M.H. Rhodes was bidding on a New Haven contract. A letter to the editor (Hartford Courant) that summer resonates in a way things probably shouldn’t eighty years later: “This is the old story of Connecticut’s hesitation complex. Over in New York State they like that Hartford meter. Now, it may be, in the course of time, that Connecticut may get just a trifle enthusiastic over a good Hartford contrivance.”

In August 1940, there are still requests for the six-month trial installation. With this stalled, Hartford’s Chamber of Commerce, in October of that year, raises a stink. They claim to be neutral on the matter, but note that the Christmas shopping season is quickly approaching, and they worry about these meters launching at the most frenzied time of year. This seemingly jolts the politicians, for a moment, anyway. In mid-November the Board of Aldermen (City Council) inches forward. At this point, there’s no point causing chaos among holiday shoppers. The matter is brought up again in late January 1941. From there, the Police Board, one week later, gives their seal of approval, despite thinking the City could have gotten a better deal by throwing out its agreement to purchase from Hartford-based companies. On Valentine’s Day, the Aldermen have their vote, and the next day, the mayor signed off. Finally, on the second week of March, it’s announced that Hartford will have parking meters installed in sixty days.

Two months turned into a bit more. Half the meters were to be installed by M.H. Rhodes and half by Standard (Veeder-Root). Because Veeder-Root did military work, there was space in the contract anticipating and allowing for delays. Due to national defense orders, necessary materials were tied up in wartime production.

On June 23, 1941, 700 parking meters were installed on the streets of downtown Hartford and hell did not break loose. Half the machines were penny operated for short-term parking of up to forty minutes. The other company’s machines accepted nickels and were installed in two-hour parking zones. People vandalized the meters with anything from bobby-pins to chewing gum. One variety of meter was easy to fool with slugs. Still, there were only a half dozen complaints each day about faulty meters when first installed, and as it turns out, many of those complaints were unfounded. Folks who got busted for not paying would claim the equipment was broken. It was reported in the paper that a motorist said he fed three pennies into one meter, but when the police opened it up, there were no coins to be found.

Incidentally, electric trolleys had their final runs in Hartford on June 27, 1941.

About five months into this experiment, it was determined that the M.H. Rhodes meters, 750 in all, should be replaced. The company debuted its “Aristocrat” model in Hartford, and on any given day, a handful of them would be reported as out-of-order. At no cost to the City, the company agreed to install another model that had been tested in other cities and proven to be slug-proof.

To recap, it took nearly twenty years to go from idea to installation in Hartford. . . and that was merely for a trial run.

For nearly a century, people have been pulling their hair out over parking in downtown Hartford, feeling entitled to park where they want for no cost, and looking for ways to game the system.

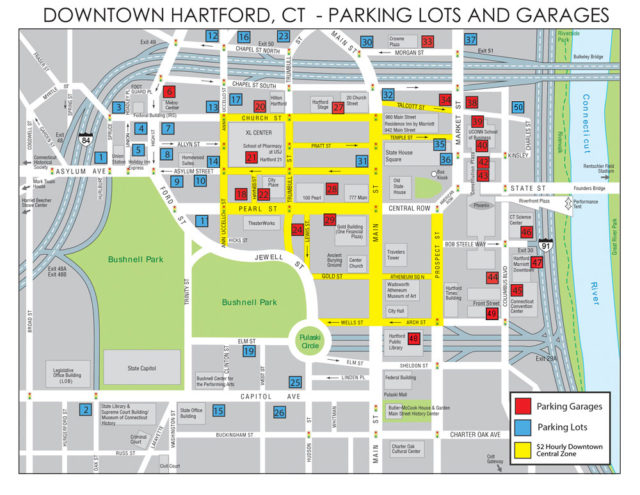

The latest changes, if you don’t bother to look at a map, can sound harsh. So, here is the map that Hartford Parking Authority has created. The streets highlighted yellow are the only ones impacted by the fee increase:

But is there not a way to dock my car without renting the space it occupies on the street? A space that could in most cases be eliminated entirely and used as a barrier-protected bike lane or perhaps a designated bus-only lane? A space that could be de-paved and planted with native vegetation?

There is.

Hartford contains many streets without metered parking or restrictions, such as residential permits.

These may not be convenient to your destination, but then, in America, we seem to accept paying more for the illusion of convenience. Prepared foods that we willingly snatch up from the farmers’ market or grocery for lunch? We buy it. Double espresso skinny lattes served in the lobby? One in the morning and another in the afternoon. Driving instead of taking the bus that goes past our house, no transfer, and stops within one block of work? That’s the norm too. If you can accept that not everything in life can or must be convenient, then you don’t have to pay money to park if you are willing walk a few extra blocks in downtown. Going back to the days before metered on-street parking, there already were studies in Hartford showing that people willingly paid more to park in a lot/station/plaza that was closer to their destination, than they were to walk three blocks and opt for a reduced rate.

Driving as the default is automatically choosing many expenses in exchange for the appearance of convenience and freedom.

“But what about the poor people?!” adds someone who normally shows no concern at all about those living paycheck-to-paycheck. Tolls and parking are peanuts compared to those other expenses, and if you want a fun activity, go find out how many hours a person has to work each year to afford the luxury of driving. Next, go see how much it costs for a bus pass. Unless you are working to reduce the cost of car payments and insurance for the working poor, please stop the faux advocating on behalf of the poor.

“But what about those with disabilities?!” asks someone who blocks curb ramps and does not bother to shovel their sidewalks in the winter. Someone with a legit placard should not have to pay extra, but neither should they be forced to park in the hinterlands because able-bodied-yet-lazy folks took all the better spots. We have technology that can solve this problem. There is no reason someone with a documented disability could not add a code when entering a license plate when “feeding the meter,” such that a reduced rate (such as the lowest parking rate for on-street parking) applies. If not through a physical meter, this can be accomplished through a parking app. This maintains fairness without giving lower rates to everyone. It’s also possible that reduced rates are not the answer. Free parking for those with placards, as multiple sources have pointed out, invites placard abuse by those without disabilities.

If this is all too much, you can entirely avoid parking fees by walking, biking, or riding the bus or train. Can’t cut the car cord? You can carpool and split the tab.

If you want the Hartford Parking Authority to be more transparent about accessibility issues and consider offering discounted rates for those with documented mobility issues, contact them at (860) 527-7275 or kenya.smith@hartfordparking.

Rex Fowler

Great writeup. In addition to the Parking Authority contact information noted, residents or other city stakeholders can show up at monthly HPA Commission meetings, held on 3rd Tues of each month (pretty sure time is 5:00 – info on website @ HartfordParking.com). There’s always a ‘public comment’ time on the monthly agenda. As a former commissioner I’ll add that the public input – especially the voices of non-auto centric residents – is highly valued but for too absent in discussions around parking/mobility/transit (in 8-9 years I was a comissioner we had maybe 3 meetings that a resident attended).